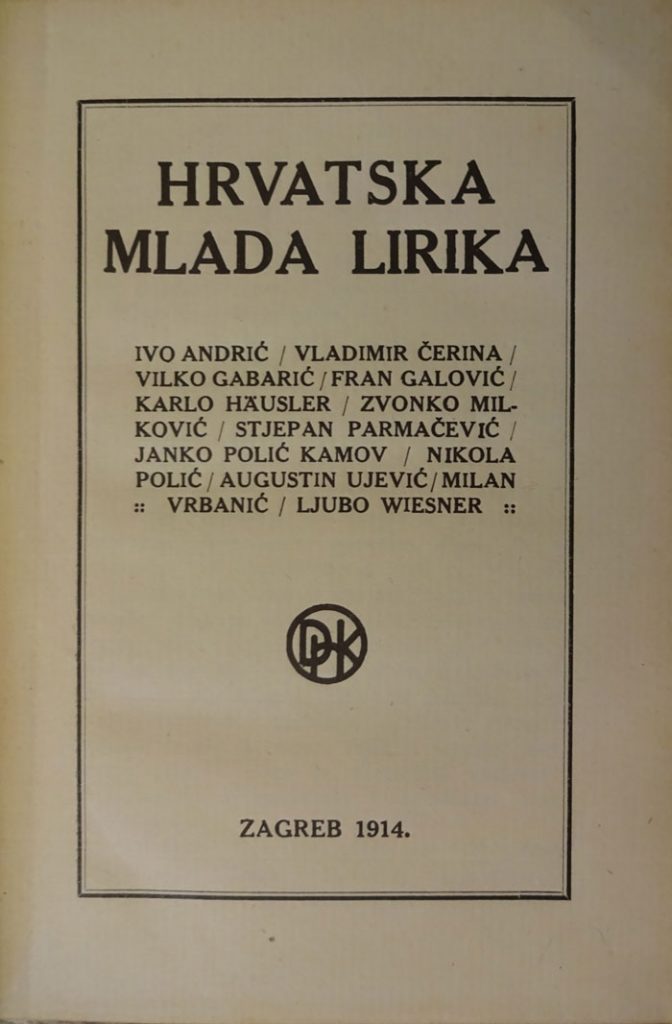

A superb new addition to my collection. An original copy from June 1914 of Hrvatska mlada lirika which features work by Ivo Andrić, Vladmir Čerina, Vilko Gabarić, Fran Galović, Karlo Hausler, Zvonko Milković, Stjepan Parmačević, Janko Polić Kamov, Nikola Polić, Augustin Ujević, Milan Vrbanić and Ljubo Wiesner.

A superb new addition to my collection. An original copy from June 1914 of Hrvatska mlada lirika which features work by Ivo Andrić, Vladmir Čerina, Vilko Gabarić, Fran Galović, Karlo Hausler, Zvonko Milković, Stjepan Parmačević, Janko Polić Kamov, Nikola Polić, Augustin Ujević, Milan Vrbanić and Ljubo Wiesner.

Category Archives: articles / članci

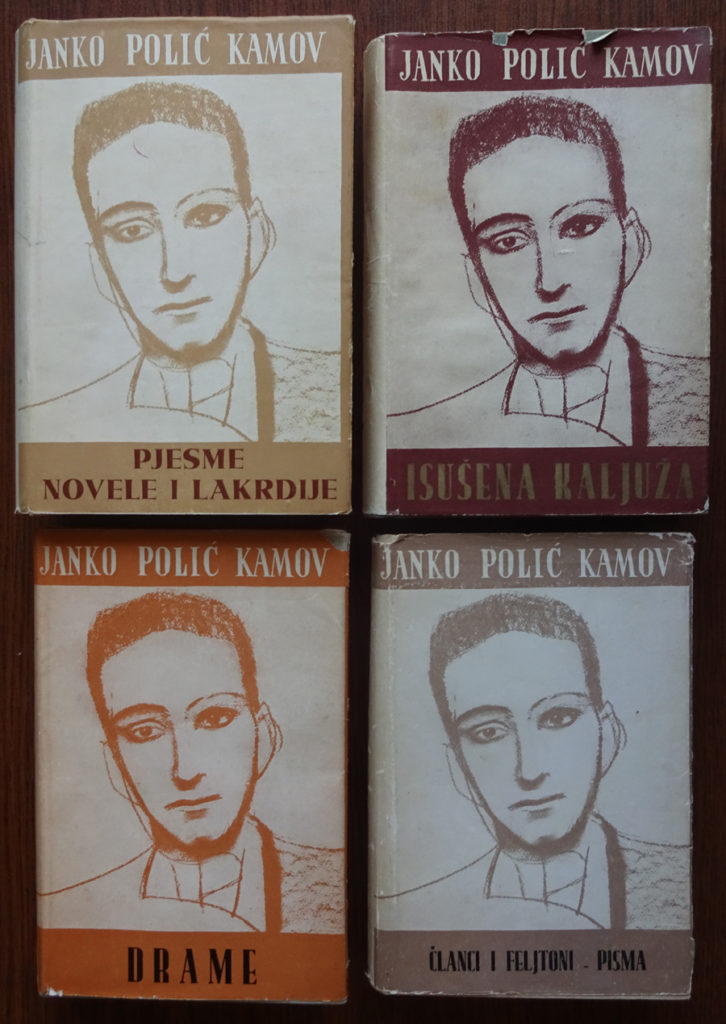

Janko Polić Kamov – sabrana djela

All four original volumes of Kamov’s work, with dust jackets. Published by the ‘Otokar Keršovani’ publishing company in Rijeka. Edited by Dragutin Tadijanović, artwork by Miljenko Stančić.

Vol. 1 – Pjesme, novele i lakrdije 1956

Vol. 2 – Isušena Kaljuža 1957

Vol. 3 – Drame 1957

Vol. 4 – Članci i feljtoni – pisma 1958

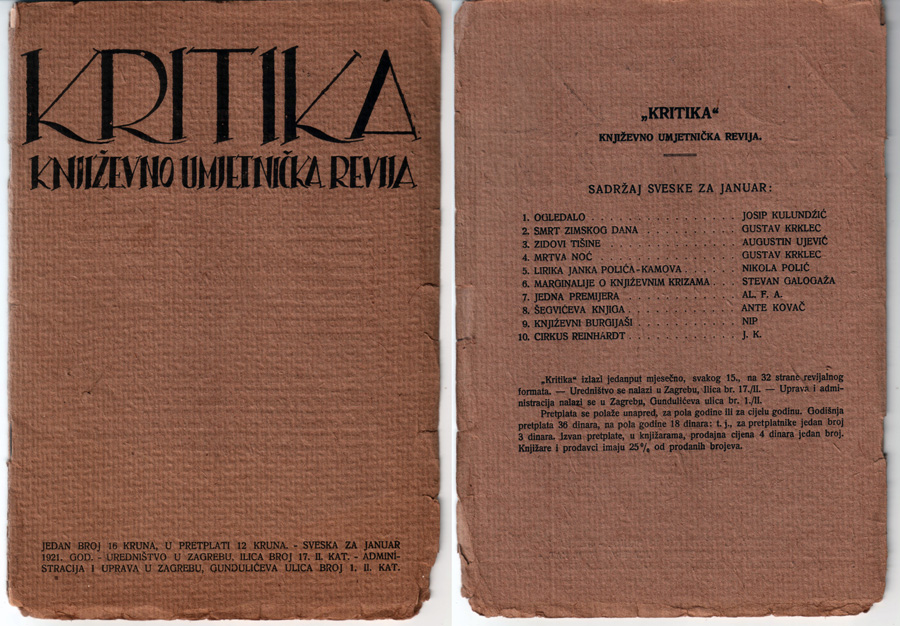

Lirika Janka Polića-Kamova 1921

Kritika – književno umjetnička revija – January 1921 edition contains part one of this essay about Janko Polić Kamov’s poetry by his brother Nikola Polić.

Kritika – književno umjetnička revija – January 1921 edition contains part one of this essay about Janko Polić Kamov’s poetry by his brother Nikola Polić.

LIRIKA JANKA POLIĆA – KAMOVA

- PLAMENI STIHOVI.

„Ja sam plamen, ja sam mač“. (Heinrich Heine)

Još prije dvanaest i više godina — kao i danas — bili su stihovi Janka Polića – Kamova predmetom čudjenja i izrugivanja baš one štampe, najširoko-grudnije pa i prama najmladjima. Stihovi ovi, još uvijek neotkriveni, uranili su prije zore u crnom, ponornom i ponoćnom kliktaju vječno neumorne, vječno žedne i vječno nesretne duše. Sudbina svih iskrenih pjevača. Sivi, tmurni je albatros to poletio grozničavim platnom razderanog neba, ne pazeći na pravilni i matematski lijet aeroplana. Za to su mnogi kazali: Evo ptice, koja leti loše!

Daleko prije Krleže, njegovih simfonija i njegovih nasljedovatelja živio je kod nas jedan — nazovimo ga tako, akoprem netačno — intelektualni, individualni, pa makar i aristokratski boljševik, Spartakus par exellence, razlikujući se od današnjih time, što u ono vrijeme ne bijaše ultrarevolucionarnost u književnosti moda, šablona i reklama.

Tada se radjala — odvojena od nacionalizma — hrvatska, upravo zagrebačka moderna, pod protektoratom Velikog Meštra Augusta Drugog, koja je dala nepismenoj našoj javnosti nekoliko odličnih i gotovih književnih profila. Ta čisto lirska Plejada, zanešena i besprikorna, umjerena i tiha, nenasrtljiva i nereklamna, pjevala je starijim ritmom, ali uvijek novim emocijama i novim senzacijama, uvijek tradicionalno vezana uz ustaljene forme, da nastavi svojim vidicima i putovima — sama, zamišljena, daleka od savremenog neukusa, bez kompromisa ali i bez zaraze. Matoš, koji je — danas to mi svi pošteno priznajemo — znatno influisao na ovu plavu i mladu radost naših dana pasjih, nije djelovao nikako na unutarnji razvitak lirike Janka Polića-Kamova, akoprem je njihov put, kao i sudbina, bio gotovo kongruentan. Konkurencija, blagorodna gospodja Jalova bila je izmedju njih bespredmetna i nemoćna. Obojica proganjana od službene, doktorske i profesorske kritike, sastali se, vodjeni podzemnim putovima čitave Evrope u Zagrebu, kod „Frankopana” dabome, a zajedničko im je bilo samo grlo i mizerija našeg tričavog i tračavog ambienta.

Grupa oko Matoša pjevala je samo lijepo i o lijepome, osvojena rezignacijom i tišinama. U lirici Janka Polića – Kamova ne osjeća se ni najtanji trag svega toga. Moglo bi se općenito reći, da on ružno pjeva o ružnome. Anacionalan i prognanik, bez doma i bez pratnje, rabiatan i krvav do srži, on nije kanda pripadnik plemena S. H. S. Grabancijaš, ali ne onaj kafana i promenada, proputovao je do svoje osamnaeste godine pola Balkana, većinom pješke, po Gorkijevom uzoru, da nakon šest godina naiđe na svoj kobni i glupavi finale tamo negdje u španskoj Barceloni, što li je?

Taj tragični skitnik bez maske nosio je po cijelom svijetu, u srcu kao i u mozgu svirepu, viseću, veliku i crnu viziju, a njegovo ostentativno komadanje duše i nerava nije bio nikad sport, literatura i danguba.

Grupa oko Matoša, otmena i izrađena, nalazila je često svoju inspiraciju u neplaćenoj bijeloj kafi i to nije vic, zaboga! I Polić – Kamov imao je svoju Muzu, manje diskretnu, ali zato vrlo, vrlo ordinarnu i brutalnu, sastojeću se od četiri prapočela svih dekadenata: duhan, alkohol, žena i histerija. Njegov su moto ova četiri stiha:

„Ja ljubim bol i patnju i gorčinu

u živoj rani!

A zaborav ću ljepšu nać’ u vinu

Neg u nirvani!“

(Strast bitka)

Alkohol je postao njegovom vitalnom potrebom, stvarajući od njega izraziti tip fiziološkog alkoličara. Svaka njegova pijača svršavaše ludim, konvulzivnim plačem, koji je ridanje, i svaka prolumpovana noć bila je jedan grč, jedna etapa, jedan fokus u ludom njegovom i bezglavom životu. Avaj, nije to rujno, rujansko, đulabijsko vino naših opjevanih Gorica! Nije to satirski, pudarski smijeh sa Vidrićevog Prekrižja i sa Haulikovog baroknog Maksimira. Nije to vino radosti, o kome pjeva Vilko Gabarić u svojem nasmijanom Vinogradu. Rakija, teška, olovna, vampirska rakija kitila je ognjenom aureolom ponorni pad njegovih ponoćnih strofa. To je lirika mȍre, što mori modra, muzička i mirna morâ. To su vizijski grčevi, okovani histeričkim plačem kao krvavi, razulareni bičevi:

„Nakvašeno, crno platno kožom

joj se zmijski svija

i kroz njega trzaj mesa u

ružičnom dahu sija.

To je žena trudnih sisâ

što sa neba sapu traži…

a morski je cjelov pljuska i grebeni nokat draži“.

(Voluptas)

Taj nas nenaravni, ali zdravi perverzitet malo zbunjuje, kad saznamo, da je to pisano u doba, kad se inače pjevaju soneti prvim naborima zaljubljenih hlača.

Samo jedna alkoholom povaljena strast kadra je rađati stihove guste i masne u embriu bolnog, bijesnog, bolesnog i bespomoćnog neutaženog užitka:

„Kroza zastor mast se cijedi ko sa smokve mast sladčine

pod raskošjem bujnog neba, po kome se priča lijeva, zalutala iz pjesama

ljiljana i cedrovine“.

(Poezija)

Pijani, crveni, krvavi i crni su to stihovi, kao boje na nekoj ustalasanoj, nemirnoj, neurednoj, burnoj i grozničavoj paleti:

„Duša dršće; to je priča zašaptala sa nebesa

u bojama, što se mijese u Gomori, na istoči,

kad se miješa karmin krvi, crno kosâ, bijelo mesa.

Duša dršće ko da akord jedna tanka struna toči

navinuta, ištipana, strašću prsti izbijena:

Bješe riječ, što se proli, klikćuć’ u šir: žena, žena!

(Poezija)

I ta pjesma (sonet) nazvana Poezija služi kao sentenca čitave te lirike, noseći u sebi sve jake karakteristike onog Polića – Kamova, koji još nije pošao na Zapad i na Jug, da svoj bujni, burni i bojovni duh smiri ironijskim rezignacijama i izigravanjem vlastitog srca. To je bila lirika bluda: čisto primarna i nejasno jasna, sa krikovima i trikovima duše što srlja, riga i pijucka.

Pjevači hrvatske mlade lirike (1908—1914) nisu nikad izravno pjevali ženi mesa, o fiziološkoj životinji i beštijici, shvatajući je tek kao kostur ili kao hostiju na oltaru svojih blijedih i bijelih vizija — i to ih je sačuvalo na pristojnoj visini, ne dajući im povoda, da se banališu i provulgare. Malo imade pjesama iz ove grupe, gdje bi fizis bio osjećaj, rima i ritam.

Drukčije je Polić-Kamov opjevao ženu, o kojoj najviše pjevaše, jer je ona meso njegovih rima i bȉlo njegovog ritma. Njegova žena ne udara nikad u pianino i ne voli da siše krv hrizantema; ne prelijeva se ona u zelenom otrovu što pada na noćno, usnulo i prigušeno svijetlo. Njegova je žena svačija i ničija, prostitutka iz najcrnjih dna života, što draži, svija, kida meso ispija mozak. To je persiflaža Turgenjevljevih Liza i Gjema, Dostojevskijevih Aglaja i Sonja; ona se približava Carmeni, crnom kriku seviljske svile i omamnom dimu Belladonna cigarete.

„Amo te ženo jeftinog mesa i skupog plača,

s haljinom trulom što vjetar snese ljudskog sred drača;

umor je zadro pospane crte na tvome oku,

a muški prsti modrice tupe po tvome boku’,

na tvome mesu svi smo mi pošli koracim’ grubim

i naše stope pričat će svijetu kako se ljubi.

(Blud duše)

„Dođi o trinaestljetna s valovljem nabrekle kože

ko koža napete svrži,

o živo takni me meso i s puti podatnom tvojom

i ovo savjesti sprži“.

(Krik)

U istom posvećenom hramu, u toj tišini tišina, sluša on krvavo golicanje bluda, grijeha i mesa:

„Orgulje bruji hramom,

a ženska grla raskvašena s poja

po njemu srču samom.

O nema stvora toga,

što ženskih struna ne bi lizno zvuka

u hramu istog Boga!“

(U hramu)

U ovim se pjesmama ništa ne retušira. Ovo je sve snimljeno na licu mjesta, u punokrvom nekom transu. Suvišak potencije, koji izbija poput čira.

Ali on nije uvijek napeto griješan. U časovima dobre volje on će zapjevati i Radičevićevim žargonom:

„O tuda prođite noškom: čarapa obijest joj zakri i none u crno zavi;

Planut će eter, kad proljet izdane požudno sapu i suknje o tijelo savi.

Šuškat će daleka priča: košuljom ovita tankom kroz goru prošla je dijeva

i tud je prosulo nebo i suze i podsmjeh i ljubav

i po njoj rosulju lijeva!”

(Nova proljet)

Samo onaj pjesnik, koji od iskona nosi povrh svih životinjskih ekscesa, u orgiji plamena, visoko gore, uvijek gore i gore jedan bludni, sveti i griješni vjeruju, kadar je da završi knjigu pjesama potresnim i ciničkim grčem poput Polića – Kamova, te svoju Golgotu krvi, požara, mesa, duše i nerava zaključuje đavoljim krstom Ridanjem jedne bludnice. Začepite uha, vi blijedi i eterni! Zakrilite oči vaše, mili i slađani! Okrenite se u grobu, vi, te u miru počivate! Pjesnik, pošto je slomio korbač na šiji glatkog i jeguljastog Snoba, pošto je pljunuo, formalno pljunuo na sve lijepe i nebeske vidokruge, te nakon što je prouzročio skandal, javnu sablazan, pada k nogama jedne jadne, ordinarne, glupe i zaražene bludnice. Ne iz prkosa, već zbog neke unutarnje, nesavladive i vizionarne ljubavi. On laže, kad se upoređuje sa Raskoljnikovom, ne iz proračunanosti, već iz samilosti prama sebi: on ljubi bludnicu, ženu na križ pribijenu, on ljubi sve ono vanzakonsko. Braća, čudna, čudna braća. Taj konačni rušeći povik nije kombinovan. Doživljeno je to, krvavo doživljeno. Crni taj liričar nije pjevao ženi obligatnim i mirisnim pervezitetom D’Annunzia iz brijačkih i modnih salona; njegovo ženstvo nije parfimisani žargon neumrlog Marcel Prevosta; nije ni pikantni sos za komije i sobarice Guy de Maupassanta. Taj gusti, masni i čemerni slador zalutao je tamo negdje sa biblijskih obala Salamunove pijane pjesme nad pjesmama. Vreli, uzavreli potok pobunjene krvi, što teče i nikad ne prestaje. Ta je dekandentska lirika — prepotentna i taj paradoks spada među aksiome, kad se citira ta neburžoaska i nesalonska lirika.

Histerija bauči i strahuje tu prekidanim i neuređenim ridanjem i izbitim, rastrganim smijehom, te siječe i reže njegove tanane, fine, ženske i razbludne usnice. Jedno nemirno sunce vise pred tim crnim Bosjakom, te poput Stanka Vraza ne poznavaše kompromisa između pjesme i života. Život je pjesma, pjesma je život. Dok i današnji književnici posjeduju spašenu životnu egzistenciju, Janko Polić – Kamov nije bio niti korektor. U pjesmi je živio, pjevajući kroz cijeli život nonšalansom La Fontaineovog cvrčka. Pitanje hrane, novca, odijela, stana i kuće bilo je tako daleko od njega, pa pošto je izdurao i najjadnije dane, plašila ga je samo pomisao na mir, dom i sitost.

Tom pjesniku, dalekom od svih koterija i škole, osporavahu pravo pjevanja, upućivajući ga na novinarstvo, na fejton, na bablju republiku. Po shvatanju kritičara, bilo je to njegovo „pravo polje rada”. Koliko kuriozne gluposti i stupidnog prenemaganja bogom nadahnute i na čast doktora promovirane kritike. Još i danas nekoji kritičari drže i Matoša lošim pjesnikom, držeći se valjda one „kritičar je gospodin koji se pokadšto miješa u ono, u što se ne razumije”. (S. Mallarmè.)

Polić-Kamov dao je svoje najpersonalnije, najkamovskije radove upravo u lirici, ne imajući preteča, počevši od sebe samoga. Ta elipsa bila je bez fokusa i jakost izraza njegovog stiha nije ni manja ni slabija ni providnija od najjačih verzova S. S. Kranjčevića, nadmašivši i autora Mramorne Venere svojim rapsodijama na prebitoj harfi (S gladi, Sunce, Dan gospodnji i t. d.)

U stvaranju silno nejednak, kao oluja što nosi na svome krilu tišinu i grom, on će nakon sadističkog buncanja zabugariti bukoličkom finesom razmaženog i suptilnog pjevača:

„Pod sunčanom krošnjom od zlatnijeg granja

Ko prašak im zlaćani list —

Poneso se smiješak što cjelove pruža,

a cjelov i draškav i čist.

I zadrhta atmos što pobud raznosi

i poljupce baca ko lud

i reko bi: negdje s plamtećega boštva

talasa se nečija grud.

(Nova Proljet)

Nije li to — čudno — kristalna slika vedrine i krajobraza:

„Cisto je nebo ko djetinja sanja

ko crno s ptičijih oči;

a sunce s dražesti mirisnu blagost

kroz oblak modrine toči“.

(Nova Proljet)

Ali tih svijetlih momenata ima malo kod njega.

Velika je griješka, upravo znak katastrofalnog i fatalnog neshvatanja, što gotovo svi nazrijevahu u njegovim stihovima ideju, tendensu i uvodni članak za anarhistična glasila. Pjesma ne pozna ideje, pa bila ta ideja i najbizarnija. Pjesma je samo izraz — kap sunca ili kap otrova. U pjesmi je Bog ili Ahasver. Metafizika ili rusvaj. Pjesma može biti plava, modra, crna, crvena, siva, ljubičasta, ali nikad komunistički — crvena, anarhistički — crna, nacionalno — trikolorna, naivno — plava i t. d. Takve pjesme uopće nema, a onaj, koji traži utilitarski ili revolucionarni monstrum u poeziji, neka traži i halbcilinder na olimpijskoj i prozirnoj glavi Monne Lise. Pjesma je tu radi pjesme, a žalosne su ambicije onih, čije stihovi imadu zadaću, da ruši sisteme. To su stvari Tolstoja, Lenjina, Radića, Bogumila i prvih kršćana.

*

* *

Ispitana Hartija i tragični psaltir Psovka natrpani su abisnom bujnošću jedne crne, otrovane, beskućne i besnene lirike, koja nikad, vaj nikad ne zna za samotne i tihe senzacije uspavanih, muzičkih soba, kad pianino šuti i žuti se miris muti u miru zlaćanih mušica, u odsjevu slika i u bolovima strasnog jorgovana. Taj Ahasver sekundirao je moguće i besvijesno Cvijeću zla, samo što mu manjka linija, mjera i zlatni rez Bauderaireove strašne i tanane, muzičke ruke, koja će istim zamahom pogladiti zelenu kosu i savinuti gvozdenu šipku. Mi nemamo ni danas simpatičnih nasljedovatelja te poezije, koja je sakrivena u nas. Marjanović ga je jedini bez viclanja primio u ono vrijeme, prigovarajući mu ipak rimama, izrazu, stilu, dikciji („Suvremenik“ 1907.) ne znajući, da ovo nije knjiga za sladokusce, te da u tim stihovima nema spomenarske, secesionističke, donhuanske i zlatousne vibracije Xeres de la Maraja, monumentalne i dosadne širine Vl. Nazora i usiđeličkih suza Mihovila Nikolića i D.D. Domjanića.

Polić-Kamov nije kumovao mirnoj, modroj lirici, koja smatra svaki stih jednom cjelinom, jednom gotovom vizijom, jednim savršenim i svršenim unutarnjim titrajem, ukratko: jednom kombinaciom. Mirna je lirika našla svoj klimaks u pejzažima, harmoniziranim i jedinstvenim Wiesnerovim sonetima. To je život u košnici, deputacija k seoskim tornjevima, muzika sjenâ zastora i zvončići neba. Drukčija je arhitektura stihova Polića – Kamova. Njegova čitava knjiga, pa da je napisao i deset knjiga, sve bi to šumilo pritajenim orkanom, vrludavim strujama, razbješnjelim valovima jedne jedine pjesme, jednog jedinog stiha. Jedan njegov sonet nosi teret jedne jedine riječi i cijela je ta lirika ispravno okrštena štipajem. Da se jasnije izrazim: nije uzor-pjesnik, ne ulazi ni u koju antologiju, nije akademik i deklamator. Ovo nisu stihovi za recitaciono veče. Do smiješnosti katkad subjektivan, personalan do ekstrema uvijek, smatra knjigu vulgarnom i formalnom ispovijedaonicom, gdje je on, autor, i ispovijednik i griješnik, a čitaoci sveta inkvizicija. Ta je ispovijed zaglušni krik, od kojega će puknuti bubnjić u otmjenom uhu g. Popovića ili će pozliti ciklamskom Domjaniću.

Progonio ga je ovijek onaj krvavi, neboderni krik Marijev iz Tragedije mozgova: Probudite se živ u grobu! – kojim je zanosno i uhodrapateljno završio i Psovku. Ta grozna, strašna i crvljiva vizija, ta Poe-ova romantična i groteskna senzacija provlači se cijelom ovom lirikom, koja se nikad i nikad ne odmara u sjeni vrbinih pramenova i koja nikad ne ugleda kućnog praga obećane hemlje. Bez doma. Bez domovine. Bez ičesa. Bez korijena. Bez sidra. Ukleti Holandez. Jedna neugašena, žedna i bijedna želja, čežnja za eksploziom, za praskom, za gromom, za požarom, za provalom vulkana. Sve to bez futurističkih snobizama. To su pupoljci na majskoj, procvjetaloj svrži otrovanog, prokletog bilja, a prsnuvši, cijedi se iz njih paklena, crna i crvena smola. Odatle i indignacia ondašnje publike, te sitna, sita i žabarska psikaše nad ovim prvijencem čistog, nelicitarskog srca gospodina Bosjaka, koji ostade uvijek Gosparom. Ista nabikulenska i dembelska čeljad prošla je cinički, triumfatorski povrh umornog i viteškog srca Lazara Heine-a, te u smrtnom hropcu žali, što čovječanstvo nema jedne glave, pa da mu pljune u lice crnu, mrtvačku pjenu.

Prem nije poznavao Heine-a, nabasat ćemo često u Ištipanoj hartiji na čisto hajneovske šlagere, koji imadu katkad onu ženskiju od ženâ ciničku zlobu, ujed i frivolnost. Primjerice pjesma pod mističnim naslovom P. S. ima intonaciju, kao i ugođaj autora Buch der Lieder. I u Novoj proljeti kao i u „Mrtvoj Diani” viri ovaj umorni, žalosni i ružni žalac:

„Sjećaš li se? Nova proljet ponijela me k našoj klupi,

po kojoj su sjele sjene:

oličiše novom bojom i nasuše gustim pijeskom

sve što bješe uspomene.

A meni se nešto misli nasmijava crnim mozgom

ko kad jesen lišće mota

i pomišljam, bogzna tko će, da se tvoga hvata pasa

da te ‘nako opet smota!

O, ne drhti! Nije prezir! Negda bijah — znaš me dobro —

preko tebe težak i ja!

A sad možda kumpanija, da, i cijela regimenta

nije teška kad te svija!“

(Nova Proljet)

Svinjarija! Kaj ne? Praštajte, gospodo suci, moraliste, bašibozuci i eunusi! I Magdalena je griješna, a Polić-Kamov oprao je taj cinizam životom i jednom od svojih najumornijih, najljepših nostalgičnih pjesama Kitty. Ovi su nedelikatni, soldački stihovi skrojeni prokletstvom i nije nikad ružan onaj, koji diše previše iskreno. Taj cinik nije, nije cinik, jer je prošao kalvariju srca i pakao duše.

Ta drhtava, razderana i carmenska muzika ponoćne pohote ne zna za blage i tople nijanse pastela i akvarela, jer se ruši u nekom divljem i crnom prahu beskonačne disharmonije, koja je vrlo daleka od drakonskih zakona gospodina Bacha, Johana Sebastiana. Što bi bilo od njega, da ga poznavaše Skerlić, koji je onako po prstima lupio Pandurovića i jadnoga Disa, inače dvije blage i mirne dušice.

Kad danas, nakon deset i više godina listamo tu krajnju ljevičarsku i mladenačku liriku, posrtavamo svakim stihom u ovoj današnjoj blaženoj i učmaloj, selendarskoj monotoniji. Ovi krvavi trzaji, i one crne strofe tralaliču u pijanom i nakvašenom ritmu jedne ognjene konjice, poput đavolje fuge sa bezbroj temata u vječnoj, nezadovoljenoj stretti. Jedno more žeđi. Jedan bezdan prošnja. Flauta i fanfara. Prokletstvo i šumski mir. Tonika i povećana kvarta. Evo, kako zvoni tišina u ovom labirintu:

„A glava bukti i polijetava k’ zidu,

da tresnem njome! . . .

Svet, svet je prasak, a blagosloven Gospod

u miru svome!“

(U mrtvoj noći).

On ne zna za mistiku i u noći ne vidi modru boju violončela, oboe i šumskog roga. Ne sjeća se zelenih, dubokih tišina, a mliječni, vitorogi mjesec izaziva kod njega persiflažu simbolskih i samotnih Vrbanićevih jablanova:

„U toj tmini sovuljastoj ko da lažni privid gaca

i sa sjena bezdušnijeh religije usne krive —

i u gluhu atmosferu umišljene dogme baca,

jablanovi strše u vis ko mesnate duše žive“.

(U nagonu).

Jedna negacija cijele naše lirike. Tamo od Vidrića, Dučića, Rakića, pa preko Wiesnera, Ujevića do Krleže, Šimića, Vinavera i Crnjanskog.

Kad se pojavio, bilo je u troimenom narodu duhovitih danguba, koji udariše u beskonačne burgije, neshvativši, šta više, ne pročitavši tu osebujnu i nikad neepigonsku liriku. Svaka se, pa i najboija stvarca dade izvrći ruglu, a tadanje Zeuse fejtona zbunila je i preplašila ta kuštrava. neelegantna i neštucana prilika, koja je svakom zgodom istupila smjelo, bez rukavica i bez hrizanteme u zapučku.

Bujnost, organsku cjelinu svog pjesničkog izraza kvario je često hotice i znalice nesklapnim stilističkim šiljcima. Vikao je, urlao, zaglušno, nenaštimano pjevao, bančio i strahovao u nekom herostratizmu, koji nikad i nikad nije bio poza ili gesta. Jezik, stil, tradicija, dikcija, Kosovo, Petrova gora, Croacija i t. d. bijahu mu stafažom za nemoćnike, a glupost što urla od Triglava do Vardara, slušao je u Torinu, u Barceloni, u Zagrebu i u Rimu: jer svijet je jedan. Prsnuše okviri Hrvatske, puknut će i remenje Jugoslavije, jer svijet je i opet jedan. Duša, koja živi, ne mari naći Nirvanu u drevnoj Heladi ili na tavanu kakve kamene kućice u Puntu, na otoku Krku.

Ne priznavaše a priori čistoću, plemenštinu i sigurnost stiha. Sveta Jednostavnost je njemu kao i Janu Husu znak gluposti i zlobe. Porušivši arhitekturu stiha, gubi akademsku vedrinu čiče Emersona i poeziju zdravlja, nacije i pobjede. Za Vidovdanski hram ne mari. Klasična, zvučna linija postala je bog te pita što. Ta je plamena lirika daleko od svih dobroćudnih, poltronskih forma; pa ipak je Polić-Kamov uzajmio od Dante-a tercinu, a od ostalih sonet i oktavu, valjda za to, jer ga je privlačila diabolika Dantea, Rinascimenta, papâ i kršćanskih perverziteta.

Poput Ahasvera ne zna za mir i dobrotu i ljepotu i taj čovjek morade umrijeti mlad — kao kaplja — jer je ritam svojih nerva našao u burnom udaranju bȉla, te najnormalnije udaraše stoičetrdeset puta u minuti.

(Svršetak u drugom broju).

Nikola Polić

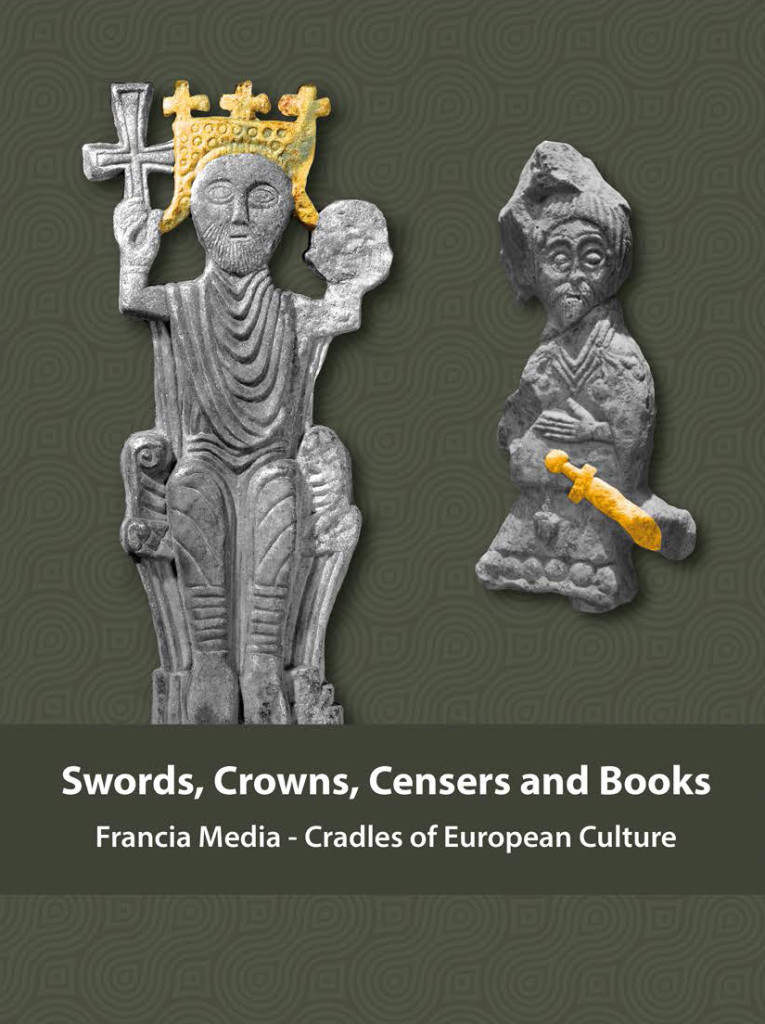

Cradles of European Culture

I am extremely proud to have been involved in the Cradles of European Culture project which involves nine of today’s European countries, which during the Early Middle Ages were part of the Kingdom of Francia Media (Middle Francia). The very impressive publication Swords, Crowns, Censers and Books is a contribution to this important project published by the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Rijeka and edited by Marina Vicelja-Matijašić. Over 432 pages it details many archaeological sites and investigations throughout Europe, including the important Croatian site of Crkvina – Biskupija near Knin. I worked as the language editor on the English texts provided for the book by contributors from all over Europe.

I am extremely proud to have been involved in the Cradles of European Culture project which involves nine of today’s European countries, which during the Early Middle Ages were part of the Kingdom of Francia Media (Middle Francia). The very impressive publication Swords, Crowns, Censers and Books is a contribution to this important project published by the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Rijeka and edited by Marina Vicelja-Matijašić. Over 432 pages it details many archaeological sites and investigations throughout Europe, including the important Croatian site of Crkvina – Biskupija near Knin. I worked as the language editor on the English texts provided for the book by contributors from all over Europe.

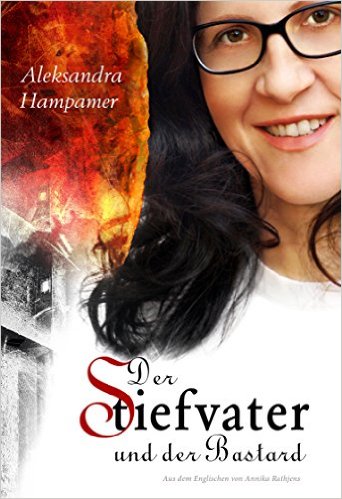

The Stepfather and the Bastard – novel translation

‘The Stepfather and the Bastard’ by Aleksandra Hampamer (original Croatian language version ‘Očuh i kopile’) is the latest book by this author from Čakovec. I am very happy to have translated this novel into English.

‘The Stepfather and the Bastard’ by Aleksandra Hampamer (original Croatian language version ‘Očuh i kopile’) is the latest book by this author from Čakovec. I am very happy to have translated this novel into English.

This is a harrowing story about the life of a young girl, Aiya, and an old lady, Tara. While Aiya suffers beatings every day from her stepfather, Tara tells healing tales that help her and many others to overcome the fear and loneliness can be present in any family behind closed doors. After many years the two old friends meet when Tara is nearing the end of her life. Told through the autobiographical narrative of the author’s childhood, the tales speak of a battle against domestic violence, and shed light where darkness blocks the way of love and the courage for change, forgiveness, compassion and support.

This is the first novel that I have translated and I am glad to have had the chance to be involved in such a brave, heartfelt and touching story.

The book is available via Amazon, as a Kindle edition here: ‘The Stepfather and the Bastard’

I am very honoured to have had my English translation used as the basis for the German language edition ‘Der Stiefvater und der Bastard’, which was translated by Annika Rathjens. It is also available on Amazon here.

I am very honoured to have had my English translation used as the basis for the German language edition ‘Der Stiefvater und der Bastard’, which was translated by Annika Rathjens. It is also available on Amazon here.

Kisha – the umbrella you’ll never lose

I’m very proud to have been involved in the world’s first Bluetooth technology umbrella, developed in Rijeka.

The hi-tech, top-quality umbrella has an in-built chip which uses Bluetooth technology to connect to an app on your smart phone. In this way it will alert you if you walk away or forget your umbrella wherever you are. Plus it also gives you the weather forecast so you’ll know whether to take your Kisha umbrella with you when you go out.

It has been developed by a team in Rijeka and I helped them with the English language of their app, website and supplied the voice-over for their promo youtube video above. 🙂

It has been developed by a team in Rijeka and I helped them with the English language of their app, website and supplied the voice-over for their promo youtube video above. 🙂

Psst! If you were wondering why they chose the name “Kisha” – in Croatian the word (spelt “kiša” and pronounced “kisha”) actually means “rain”. 😉

All the info, how to order an umbrella and download the app is on their website here

All the info, how to order an umbrella and download the app is on their website here

Kisha umbrella survives the Adriatic’s infamous “bura” wind in Rijeka harbour:

Kisha umbrella test in Poland:

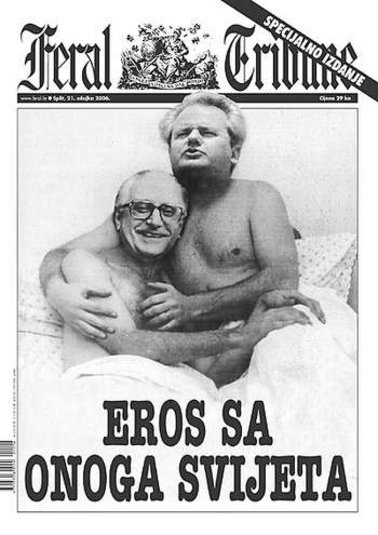

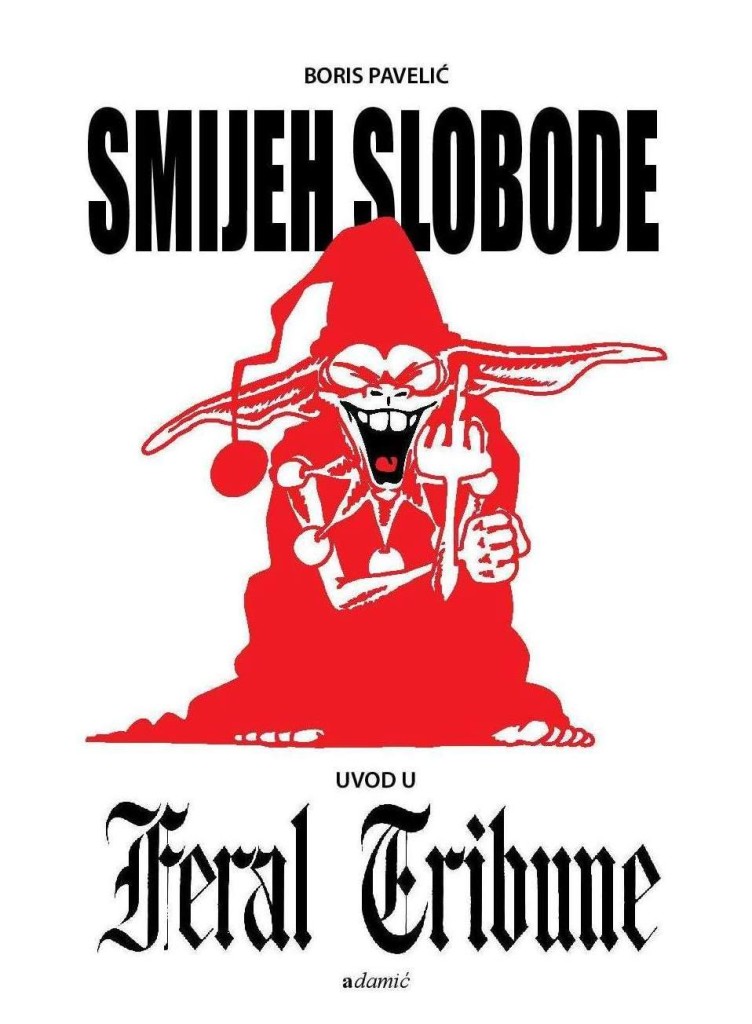

Feral Tribune – book summary

The book ‘Smijeh slobode – uvod u Feral Tribune’ (‘The Laughter of Freedom – an introduction to the Feral Tribune’) by Boris Pavelić describes and explains the 25 year old cult political-satirical newspaper the ‘Feral Tribune’, based in Split. It was published from 1983-2008 in various forms and billed itself as a “weekly magazine for Croatian anarchists, protesters and heretics.”

The book ‘Smijeh slobode – uvod u Feral Tribune’ (‘The Laughter of Freedom – an introduction to the Feral Tribune’) by Boris Pavelić describes and explains the 25 year old cult political-satirical newspaper the ‘Feral Tribune’, based in Split. It was published from 1983-2008 in various forms and billed itself as a “weekly magazine for Croatian anarchists, protesters and heretics.”

The publication won international awards in the 1990s but slowly went out of circulation – this book studies the history and value that it had and still has in modern-day journalism.

The book is only available in Croatian and I translated the summary into English. It is hardback, has 688 pages and its ISBN: 978-953-219-492-0.

It is published by Adamić d.o.o. and is available in shops and via the publisher’s website here: http://shop.adamic.hr/index.php

Interesting historical facts about Rijeka – European Capital of Culture 2020

Some historical facts about the city of Rijeka – the European Capital of Culture in 2020

Did you know…?

– in Rijeka in 1909 the first Croatian feature film was made.

– the first television aerials in Croatia were placed on the roofs of houses in Rijeka.

– the first kidney transplant in the ex-Yugoslavia was performed in Rijeka, in 1971.

– in the Arctic there is a piece of land named after Rijeka (Cape Fiume).

– Robert Ludvigovich Bartini born in Rijeka was an accomplished aircraft designer.

– in Rijeka the trajectory of a gunshot was photographed for the first time in history.

– in Rijeka the trajectory of a gunshot was photographed for the first time in history.

– the postmark ‘V’ Fiume from 1755, is the oldest surviving postmark in the Republic of Croatia.

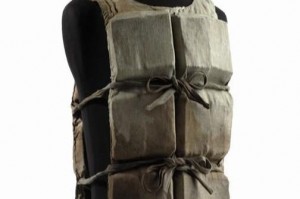

– a life jacket from the Titanic is located in the local museum. It was collected by the RMS Carpathia (the ship that saved the Titanic’s survivors) on route from New York-Rijeka.

– in Rijeka in 1786 the first midwifery school in Croatia was founded.

– in Rijeka in 1786 the first midwifery school in Croatia was founded.

– the ‘Husar’ disco club in Rijeka was the first in this part of Europe.

– that ‘Quorum Colours’/’Fun Academy’ was the first and largest Croatian underground club.

– that ‘Quorum Colours’/’Fun Academy’ was the first and largest Croatian underground club.

– the first Croatian rock band, ‘Uragani’ came from Rijeka.

– the first punk group in Croatia ‘Paraf’ came from Rijeka.

– the first punk group in Croatia ‘Paraf’ came from Rijeka.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RwmwMd96jlE

– Croatian Hip-Hop began in Rijeka.

– in Rijeka the first speedway race was held in Italy and that the founder of Italian speedway was in fact from Rijeka.

– the first psychiatric hospital in Yugoslavia was built in Rijeka.

– the oldest lift in Croatia is in Rijeka.

– the first vehicle marked “Made in Croatia” was built in Rijeka.

– the first vehicle marked “Made in Croatia” was built in Rijeka.

– that under Rijeka there is a cave which has been declared a natural geomorphologic monument.

– that Rijeka had its very own Schindler who helped hundreds of Jews.

– in 1852 in Rijeka the first gas production plant began operation in South East Europe.

– Rijeka’s rope factory is the oldest industrial plant in the city’s history.

– the first sanatorium in Croatia was opened in the district of Pećine.

– the first radio transmission in the ex-Yugoslavia was made in Rijeka, back in 1920. It was a speech by D’Annunzio.

– the first Croatian steamship was built in Rijeka and with it a regular passenger route between Senj and Rijeka was established which is considered to be the start of passenger travel on the Croatian Adriatic.

– the Croatian national anthem was written in Rijeka by Antun Mihanović.

– that French writer Henri Beyle Stendhal spent some time in Rijeka.

– that member of the American Senate and Mayor of New York Fiorello Henry La Guardia stayed in Rijeka as the US consul and played in the Rijeka football club Atletico Fiumano.

– that member of the American Senate and Mayor of New York Fiorello Henry La Guardia stayed in Rijeka as the US consul and played in the Rijeka football club Atletico Fiumano.

– that Rijeka’s Pero Radaković scored the only goal in the quarter-final match against Germany, during the Football World Cup in Chile in 1962, ensuring Yugoslavia’s 4th place, which was to be its best ever result.

– that Rijeka’s Pero Radaković scored the only goal in the quarter-final match against Germany, during the Football World Cup in Chile in 1962, ensuring Yugoslavia’s 4th place, which was to be its best ever result.

– Nikola Tesla had a sister who lived in Rijeka and that D’Annunzio’s legionnaires destroyed all her personal letters and other effects which should have been preserved for history.

– Nikola Tesla had a sister who lived in Rijeka and that D’Annunzio’s legionnaires destroyed all her personal letters and other effects which should have been preserved for history.

– Georg Ludwig Ritter von Trapp, the most decorated submarine captain of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, attended the Naval Academy in Rijeka. At the shipyard in Kantrida, where the submarines were launched, he met and fell in love with Agathe, the granddaughter of Robert Whitehead (inventor of the torpedo in Rijeka), and they married on 10th January 1911 in Rijeka. In the 1960s one of the best musical films of all time ‘The Sound of Music’ was filmed about the von Trapp family.

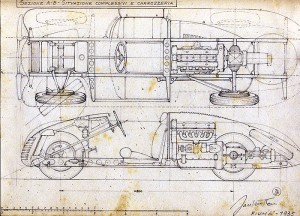

– in 1937 Gino and Oscar Jankovits from Rijeka designed, constructed and tested the first car in Croatia. It was the Alfa Romeo Aerospider. It was the first vehicle in the world with fitted door handles and lights in the chassis, the first with the steering wheel in the centre, the first with the engine placed centrally at the rear, the first with a horizontally placed radiator and it could reach a speed of 230 km/h.

– in 1937 Gino and Oscar Jankovits from Rijeka designed, constructed and tested the first car in Croatia. It was the Alfa Romeo Aerospider. It was the first vehicle in the world with fitted door handles and lights in the chassis, the first with the steering wheel in the centre, the first with the engine placed centrally at the rear, the first with a horizontally placed radiator and it could reach a speed of 230 km/h.

– in Rijeka on 9th June 1969 the first library bus in Yugoslavia began working. It visited the city’s surroundings which had no access to library facilities providing all the inhabitants with library services.

– in Rijeka on 9th June 1969 the first library bus in Yugoslavia began working. It visited the city’s surroundings which had no access to library facilities providing all the inhabitants with library services.

– in 1984 the first cash machine, ATM, in Yugoslavia was installed in Rijeka by Riječka Banka.

In 2020 Rijeka is the first Croatian city to hold the title of European Capital of Culture – the year-long programmes of events begins on 1st February – more info here:https://rijeka2020.eu/en/

Antun Barac – ‘Fiume’ in English

‘Fiume’

(passing impressions, July 1919)

by Antun Barac – translated for the first time by Martin Mayhew

Three beautiful, sunny, autumnal days. I don’t know what happened. In a single morning all the ties snapped, that were holding the voice in the throat, that loosened the links, that were chaining the feet, the heavy and rigid mask fell, that was hiding the face. A quiet whisper, which spoke curses and revealed a howl, scattered itself like a wild, holy cry of joy, whilst a hand, a pathetic hand, taught to give a servile and official greeting, extended for the first time in a bold gesture of belief and confidence in itself.

We went onto the streets, in processions, assemblies, groups and we sang and cheered. And everything was so sunny, bright and light. And everything was clear and cheerful and happy in the beautiful, clear autumnal day.

In the barracks there were soldiers, and they were cheering. In the hospitals there were wounded, and they were singing. The soldiers came out onto the streets and were firing their guns. After four blurry years it was the first time that the firing meant joy, after four sombre summers it was the first time that a bullet didn’t mean death, but life. And it was as though that shot, which was now rising into the air, was a symbol, as it rises and as it falls.

On the chests flowers and tricolours. In the windows flowers and tricolours. On the streetlamps, on the telephone poles, on the makeshift stands flowers and tricolours.

In a red, white, blue, green colour, in the grey colours of joy, ecstasy, hope and belief, on each flag, that flutters, of elation, love, sympathy and adoration, which the flag as a symbol means. In the red glow of love and brotherhood towards everything and everyone, in the whiteness of the cleanliness and sublimeness of ecstasy, hope in the new world, that was being created.

We went out onto the streets and sang. We welcomed the foreign troops and sang. We threw flowers and sang. We welcomed ships from foreign countries and sang. “Call out, just call out… Viva la France! Allons enfants de la Patrie!…” And the children of the homeland arrived, and laughed, and danced, and cheered.

“Here people just walk around and cheer and sing” – they say, wrote home one French sailor. “Viva la Yugoslavie!” His compatriots cheered – and in their scepticism and in their laughter for the sake of laughing and joy for the sake of joy we felt the first stab of disappointment and misunderstanding.

In an isolated corner an old hunched over woman was sobbing. “Woman, why are you crying?” – asked a voice – I don’t know whose, and I don’t know where from. “In every joy there is a note of pain, in every laugh a seed of sorrow”, as though replying to somebody’s voice – who knows whose, who knows where from?

Three beautiful, clear, sunny, autumnal days. Three days of song and clamour and ecstasy. And then – armoured cars, machine guns and horses on the cobblestones and pikes, stretching up high, rigidly, arrogantly. In the port heavy ships with cannons aimed at the city, on the street assault troops with helmets, rifles, knapsacks and ammunition belts.

Three beautiful, clear, sunny, days passed. And nothing to show for them. Only a difficult, long winter with clouds. Just a cold summer with raindrops, that with the ‘bura’ and rain even the tears froze. Just a gloomy spring without light or sun.

Maybe a time will come, when all the ecstasy and elation will seem ridiculous to us. Maybe a period will come, when every sense will be reduced to a mathematical or chemical formula. I only know, that even then, when I was in the height of national fervour, I felt no desire for revenge or hatred or malice – the days of the greatest joy were days of forgiveness for everything, to all who had oppressed us, days of national liberty, a time when love for everyone was the most lively, the most conscious. And in those days of intoxicated delight and love, that had boiled over, the clenched fists, clashes and attacks were the end of everything.

I don’t know what happened. In just one day with a wild roar they began to tear down the tricolours of red and white and blue, and in the windows, on the streetlamps, the houses, the buildings, the churches suddenly others appeared – red and white and green, with a star and a coat of arms. Everywhere the coat of arms and everywhere the star, and everywhere fanatic hatred in the faces and fury and poison in the looks. “Italia o morte! Fuori il straniero!” Whilst the straniero thoughtfully stops and thinks: “Who in fact is the stranger?”

In these sombre days of waiting and incertitude, desperation and zeal, it is so difficult to be alive and carry all the heavy burden of the present; however it is hardest to be human. So many times I have felt the pain and burden of life, but the worst thing was when I felt the aching shame, I didn’t feel fear for myself, but for those who persecuted us, the shame of man, that chaotic, disproportionate mixture of beast and god. The beast, wild, brutal, vicious, kicking and rearing up, and the god, sublime, the ashen sceptic levelling with it, taming or incensing it. And in the battle of animal with god like the battle of a bull with a toreador – the white, red, blue, green colours, that they have signifying a symbol, they stimulate it, intoxicate it, they extol it, bring it to an ecstasy of madness and rage. Fiume, the yellowish-grey, deceitful animal, from the eyes of which peer the envy and intoxication of excessive enthusiasm, throws itself, snapping, howling and moaning into exhaustion, until it falls bewildered, unconscious to the ground.

Therein the roar is so quiet! Therein the crowd is so uneasy and lonely. In this racket our steps reverberate so eerily. Oh, the whole of this city, whose number of inhabitants doubled in a few months, as it turned into a huge, grey, isolated monastery, where the shadows succumb to the wolf, hollow songs reverberate and the voices of muffled prayers drone. And thus it is miraculously quiet and in the murmur, so terribly calm in the constant throng.

Why call this city Rieka, when it is – Fiume. Reka, Rika, Rieka – that sounds so sweet, placid and childlike like the nostalgic “ca” and “ča” of the people of Drenova, Plase, Trsat, reminiscent of the sunny gleam of the stone walls and enclosures scattered with rocks and brambles, amongst which, in spring, blossom such beautiful and fragrant violas, a modest and shy flower. It is a city with a filthy physiognomy and with an inner self bland and murky, like the murky Fiumare canal, the dead water that cries for it. The Fiuman is a separate race, not belonging to any one nation. It is a mixture of everything that has come to this merchant city to trade – of everything, of many things. The Fiuman is both an Italian and a Yugoslav – an Italian, born of Yugoslavs and brought up as a Yugoslav, who cheers at the top of his voice: “O Italia o morte!”, the Yugoslav is a quiet and timid beast, hiding because of his interests of his national origin with a neutral, inexpressible, merchant’s sneer. Whilst the Riečanin, Recan, Ričanin – they are the masses – they are the nameless mass, who don’t ask, quantité négligeable, they are the inhabitants of the workers’ houses, basements and attics, the servants and labourers, small artisans and assistants, the masses, who have only one head, and who would, maybe, with just a single blow fall. And that is the characteristic, external image of the city – Fiume, Fiuman. And in this fatal exchange is the source of all the illusions, all the efforts and all the miserable disappointments.

Years and years of timid and quivering yearnings for the city of Kvarner and in that name I will stop with everything, that was the dearest and utmost in life – but then the bloody realisation, that it was all just a yearning for childhood, for the sea, for the days that had gone forever. Yet there is no city, there is no childhood and there is no sea. There is only Fiume and Gomila and Fiumara – a murky, stagnant mire, like a feeble residue of exacerbated human passions, without the strength that it vanishes, without the strength that it stirs up, rises, moves.

Corso. An evening stroll. In the looks a glow and depth, in the gestures a yearning and yielding to love. Yet the whole city seems to shiver from one single deep gaze, which rises from the bottom of the soul and seeps into the bottom of the soul, and the whole city seems to twinkle from love, that is only the soul, only the soul. Whilst down, in the depths, inside – ah, there is no soul and there is nothing, the base and desolation and emptiness. And the whole of this city and all these people who rousingly speak and shout and wave – the whole of this city has no soul, and everything, that moves it, is the basic animal life. And its voice is not the sublimeness of ecstasy nor the size of reproach – everything is just a roar, clamour and mania. And the moment will come and everything will boil over and everything will disappear, what froths up and what rises up – on the empty bottom will remain just Fiume, a city without a soul and without physiognomy and a notion without features.

Over five bloody years ten times in the memory of the sparseness and irritation of the nerves the city howled and ten times they changed the inscriptions and ten times in a fanatical irritation the masses passed over their old idols. Today on the ruins of everything, a fiery rage triumphs in the proud satisfaction, that with the greatest lie it refuted thousands of its little lies and that in the deafening cry it suppressed everything, that protests, that rebels. Because that cry is not a lie, because this fire of enthusiasm isn’t hypocrisy. It is Fiume and everything is Fiume. And to whomsoever this Città di San Vito belongs; whosoever flag will flutter next to the double-headed eagle with the yellow-blue symbol – will win, I’m afraid of Fiume, and with a shout of honest enthusiasm the malicious cry of a lazy and cunning animal will intervene. And that is my fear and it will be a drop of bitterness in that moment, which we will surely never live to see.

What can enthral a man in this city, in which culture and supremacy are denoted by the black marks on the walls and the holes in broken inscribed tiles? In our weakness for it there is a weakness towards one’s own past, which is contained in these pavements, street corners and quays, a weakness towards the whistle of departing steamships and the whiteness of unfurled sails, that awoke our childlike imagination and tied it to this place, that doesn’t love us. In our trepidation towards its destiny there is only the fear for those miserable, unknown, oppressed thousands, who just silently accept the blows and ridicule and the stamp of inferiority. We understand that the sinful must repent the sins and perform penance those, who have deserved it. However what did the little pale children commit that they must suppress their voices in their throats, the only one with which they are able to express the feeling of happiness in the joy and drive of wickedness in the game?

Our feeling of attachment with this city isn’t a feeling of love, but a feeling of pain, and fear, and hopelessness in the sense of a wounded animal and disgust and revulsion. Because it is just Fiume – and Fiume is not an organism, not a concept, not a soul, but something colourless and tepid and tensile, that with its odour tears at the nostrils and throat, and intoxicates and commits evil. And here nothing enthrals and here nothing is attractive. The love of this city – ah, it is an illusion, it isn’t love, but an escape from it, an escape to the blueness of the sea, the sigh of Trsat, the greenery of Opatija and Volosko and the serene vistas towards Kostrena, Omišalj, Cres and Ika. Everything that nature has warm and soothing and soft, is gathered around this city, to shield it, to protect it, to conceal it. And the reason why its poison didn’t act. In the moment when the heavy shackles fall from the chests and from the legs and from the hands and from the tongues, from all sides pale children will rush and shower it with flowers of love, forgiveness and it will forget all the insults, all the blows and all the threats.

From Školjić to Kantrida – one and the same street and one and the same image: houses without expression, without style, stores, shop windows, markets. In the place where there is only trade, all the houses are built on clear commercial principles: with the least expenses – the highest rents. Houses without physiognomy, without souls. In the city, where everything is measured purely in monetary measures, the friars had also taken advantage of the few metres of free space around the church and built umpteen little rooms for shops. Trade is not permitted in the temple, however it is better in front of and around the temple. The city of fifty thousand inhabitants did not give up one single man, whose name would be recorded in the history of culture and art, and wishing to somehow christen their streets, the fathers of the city were having to reach back for names from the mother countries: of Hungary and Italy. In a city of fifty thousand souls there is not one monument, and the only highpoints on the streets are advertising posts and lavatories – as unintentional symbols of it, as if it is the only purpose in this place. I love and appreciate trade as a means, but as soon as it becomes the meaning of life, it becomes both the negation and profanation of all higher values. And that which people would have to make them happy, to lead them ever upwards, throws them ever lower. And Fiume is deep, so deep.

Amongst its great evidence for being Italian the supremacy of Italian culture is prominent in Rijeka, the culture of the Italian is greater than that of the Yugoslav. Whilst the first glance at this city shows that it has, in general, no culture, not only of its own, but no culture of any kind, and that, which in the moment could deceive the eyes, is just glued on, that is easily washed-off by the rain or over night, when the city’s new generation is over-patriotically disposed.

The fun fairs, public houses, buffet bars, cafés, cinemas. All dirty, all abandoned, all in disarray. The dirt of the port as though it passes into the city itself, into every corner, every alleyway. This relatively large city is not capable of supporting a permanent theatre, whilst the companies, which are hosted here for a month, twice a year, can only be supported by the subscriptions of Yugoslav misers. In the place, where all the sights are just negative assets, such are the values and the two most important characteristics: Rijeka’s Gomila and Rijeka’s street gangs. The heart, the centre of the city, consisting of ancient ruins, disgusting mansions with narrow and winding streets, where the sun never reaches and where streams of undignified liquids flow freely; dangerous, dark corners, smelly inns, and women, and beggars, and drunks. While Rijeka’s street gangs they are a mighty gutter army, an abandoned mob that attacks the schiavi, that fights selflessly and fervidly for the lofty goals of the city’s fathers and less selflessly, for the needs of life. And that is – Fiume.

In the days of liberty, in the days of the universal love of forgiveness, a grey monster howled, that calls itself Fiume, with a howl of hatred and revenge. In the days, when kisses and expressions of brotherhood should have rained down, it prepared itself for secretive bites, punches and stabs. And why wasn’t the punch stronger, that is just the deceitful cunningness and feeling of weakness alongside all the abundance of gesticulation.

Is this city ours? Ours are those thousands and thousands of silent beings, who resignedly just wait, eternally waiting, thousands unarmed and unlawful, who upon the punch and the bite correspond with a speechless look, who upon an energetic nod from their masters sign up dutifully and without opposition, not asking: “Where to?” – It doesn’t matter, what they’re called. In the ascertainment of their anguish there was the justification of a love for them, from their speechless mouths comes a call for resistance, for rebellion, for liberation. And that is why, as their national consciousness is not strong, as the term of Yugoslavism has not developed in them yet, their pain is even stronger: it is the consciousness, that despises them, that brands them without reason, without cause, that they oppress the concept of man in them. Yet theirs is the main feeling, the feeling of shame, that they belong to a common creed unlawful, powerless, weak – and with the sense of the joy of life is mixed some dreary feeling of their own inferiority, a state of neglect before the mighty.

Is this city ours? Ours are those thousands and thousands of silent beings, who resignedly just wait, eternally waiting, thousands unarmed and unlawful, who upon the punch and the bite correspond with a speechless look, who upon an energetic nod from their masters sign up dutifully and without opposition, not asking: “Where to?” – It doesn’t matter, what they’re called. In the ascertainment of their anguish there was the justification of a love for them, from their speechless mouths comes a call for resistance, for rebellion, for liberation. And that is why, as their national consciousness is not strong, as the term of Yugoslavism has not developed in them yet, their pain is even stronger: it is the consciousness, that despises them, that brands them without reason, without cause, that they oppress the concept of man in them. Yet theirs is the main feeling, the feeling of shame, that they belong to a common creed unlawful, powerless, weak – and with the sense of the joy of life is mixed some dreary feeling of their own inferiority, a state of neglect before the mighty.

Whatever happened, whatever the fate of this city, I will not complain and I will not pity those, to whom the street corners, the banks, the ships and the warehouses belong. Alongside all of their Yugoslav tricolours, were also the Fiumani, and in their pre-war silence and chivalrousness were hidden the subterfuge and calculating attitude of the merchant, who goes just for the money. I won’t grieve for them nor for the legion of those, who over three lovely autumnal days cheered, sang and carried banners. I will only grieve for the pale little people, as their half-spoken “ča” chokes in the instinctive fear before the sharp glance of contempt and superiority…

Long, difficult months of waiting. Events, attacks, parades. Soldiers, soldiers, soldiers. Italians, French, Americans, English, Indo-Chinese. Ships, automobiles, aeroplanes. Carabinieri, bersaglieri, granatieri. Infantry, sailors, lancers, gunners. Crowded and mixed and multi-coloured. Smugglers, detainees, fugitives. And the inns and basements reverberate and glass shatters and girls scream, and blood, wine and champagne flow. Fiume goes crazy and howls and rages.

Yet that’s what it wanted and so sullenly and so sombrely. Like the shadows we loiter only around the corners and we disappear in the corners. Whilst the sun stings and the truth stings. However, the shame against man stings the most of all, for man, as he oppresses his own brother. Of all these people of various colours and uniforms the most likeable are the Annamese (Vietnamese from the French peacekeeping forces), yellow, silent, mysterious, calm creatures with a sick nostalgia for the East and a blunt lack of understanding for all of this colourful, noisiness and craziness. Why are they here and for what use is the secret, eternal pain for the motherland? The same feeling in them, that they protect us, and in us, that they protect. A feeling of pain, shame, submissiveness, disgrace.

Mornings and afternoons and evenings pass. And nights fall, long nights without sleep, when below the windows the hooves of horses clatter as they pass by, heavy cannons boom, the steps of soldiers reverberate. And the city stays silent and the river stays silent, and the sea, in a troubled uncertainty. Just above the houses glimmer the large, light letters: Viva Fiume italiana! And the shining sign and the shining star, so that the brothers can see on the other bank. And they in despair and hopeless expectancy hide their heads amongst the pillows, so they see nothing, so they hear nothing, so they feel nothing. And everything is dead, rigid, uneasy. And everything is sleepless yet in a dream, without a break, without rest, without peace, without joy.

It just sleeps like a fatigued beast, dreaming maliciously and in that sleep of new bites and stabs, the grey formless masses, Fiume sleeps, a city without soul and without physiognomy.

*******

Sva prava pridržana / All rights reserved.

Antun Barac (1894 Kamenjak near Crikvenica – Zagreb 1955) was an important literary historian and writer, who was an advocate for the publication of Janko Polić Kamov’s works. In 1917 he established the influential publishing institute ‘Jug’ in Zagreb with other writers. Amongst the books they planned to published was Kamov’s only novel Isušena Kaljuža written from 1906-1909, but this never happened.

Antun Barac (1894 Kamenjak near Crikvenica – Zagreb 1955) was an important literary historian and writer, who was an advocate for the publication of Janko Polić Kamov’s works. In 1917 he established the influential publishing institute ‘Jug’ in Zagreb with other writers. Amongst the books they planned to published was Kamov’s only novel Isušena Kaljuža written from 1906-1909, but this never happened.

Barac spent the unsettled period after the First World War from 1918-1924 in Sušak (the eastern part of today’s Rijeka) working as a professor at the secondary school. During this period he wrote this short, stark, even poetic essay Fiume, in which he describes the unpleasant events and experiences in the city of Rijeka at the time of the arrival of foreign peace-keeping troops whilst the city’s fate was being decided in post-war negotiations, and just upon the eve of the arrival of D’Annunzio and his soldiers. It is interesting to note that Barac was most likely reading the still as yet unpublished manuscript of Kamov’s Isušena Kaljuža during this period and that it may have influenced his writing of Fiume. This text was first published in the journal Njiva in 1919.

Barac was also the originator of the idea to publish a collection of the complete works of Janko Polić Kamov, which finally saw the light of day from 1956-1958, amongst which the novel Isušena Kaljuža was printed for the first time almost 50 years after Kamov wrote it.

Thanks to Igor Žic

Andro Vid Mihičić – poetry in English

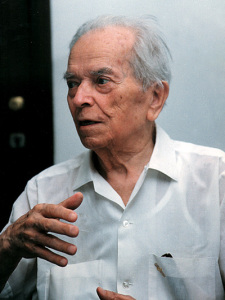

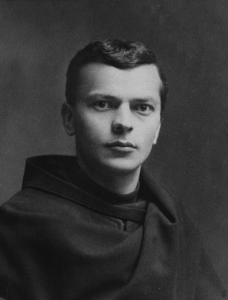

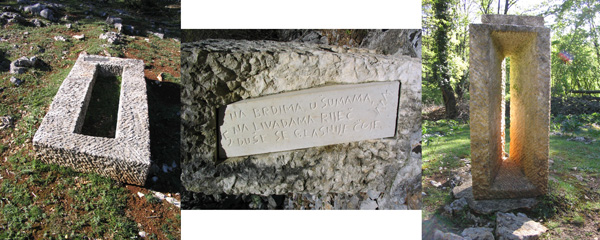

Andro Vid Mihičić was born in the idyllic village of Beli on the island of Cres on 26th March 1896. He was an art historian, professor and poet. At an early age he enjoyed nature and philosophy. He was educated in Paris as a Franciscan Tertiary Friar and there he graduated from the Faculty of Art History at La Sorbonne. During the Second World War he joined the anti-fascist movement as a military chaplain. In 1944 he left the Franciscan Order. After the war he was chosen as professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb. He only began to publish his poems when he was 92. Here are some excerpts from his beautiful short poems, translated from the original Croatian into English, which accompany the sculptures of Ljubo de Karina on the trails in the forests of Tramuntana on the northern part of the island of Cres.

Andro Vid Mihičić was born in the idyllic village of Beli on the island of Cres on 26th March 1896. He was an art historian, professor and poet. At an early age he enjoyed nature and philosophy. He was educated in Paris as a Franciscan Tertiary Friar and there he graduated from the Faculty of Art History at La Sorbonne. During the Second World War he joined the anti-fascist movement as a military chaplain. In 1944 he left the Franciscan Order. After the war he was chosen as professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb. He only began to publish his poems when he was 92. Here are some excerpts from his beautiful short poems, translated from the original Croatian into English, which accompany the sculptures of Ljubo de Karina on the trails in the forests of Tramuntana on the northern part of the island of Cres.

Testament I have no sons, no grandsons. To whom shall I leave my poem and my dream and the great wings of foreboding which in infinity flap? To you, my people! From you I sprang, through you I return to immortality so I flow through the underground again with the flowers in the fields I blossom and build stalactites underground for a temple of beauty and dreams. All to you and only to you, my Croatian people.

When I arrived in Beli it was dark. Stables full of dying sounds. Gorges and glens full of ghosts and spectres, the sea full of stars and the sky, full of deep secrets and an infinite blueness.

When I arrived in Beli it was dark. Stables full of dying sounds. Gorges and glens full of ghosts and spectres, the sea full of stars and the sky, full of deep secrets and an infinite blueness.

Have you ever heard flowers talking at night? Around us everything is full of secrets. Even in a rock life is hidden – nothing is dead.

Have you ever heard flowers talking at night? Around us everything is full of secrets. Even in a rock life is hidden – nothing is dead.

Life is also hidden in a rock, dreamt of, but it’s there. Hit it, you’ll hear its heart beating.

Life is also hidden in a rock, dreamt of, but it’s there. Hit it, you’ll hear its heart beating.

What are you looking for – a flower asks me – In the mist in front of the ruined houses In the darkness even trees pray. Talk to me, wind, about the sun On the field.

What are you looking for – a flower asks me – In the mist in front of the ruined houses In the darkness even trees pray. Talk to me, wind, about the sun On the field.

Nature cleanses the man, It fills him with power of the mind, instinct and the forces of life, And reveals a secret of modesty.

Nature cleanses the man, It fills him with power of the mind, instinct and the forces of life, And reveals a secret of modesty.

On the cliff near my village griffons build nests into the sky they dive they circle they rise up and defy the storms.

On the cliff near my village griffons build nests into the sky they dive they circle they rise up and defy the storms.

*****

His poetry accompanies the sculptures of Ljubo de Karina on the eco-trails in the forests of Tramuntana on the northern part of the island of Cres.

He died on 26th January 1992 in Mali Lošinj.

He died on 26th January 1992 in Mali Lošinj.

A bust of Andro Vid Mihičić is placed on the side of the parish church in Beli in his honour.

A bust of Andro Vid Mihičić is placed on the side of the parish church in Beli in his honour.

Full texts:

The Testament

I have no sons, no grandsons.

Whom shall I leave my poem and my dream

and big wings of Foreboding

that wave in the infinity?

To you, my people!

From you I sprang,

through you I return to immortality

to ring through the underground

and like a flower blossom in the fields

and build the shapes in underground

for a temple of beauty and dreams.

All to You and only to You,

my Croatian people.

————–

When I arrived in Beli

it was dark.

Stables full of dying sounds

Gorges and glens full of ghosts and phantoms

the sea full of stars

and the sky

full of deep secrets

and indefinite blueness.

————–

Kneel before the truth,

Knock and pray before the door of the secret.

————–

Roads and dreams and sorrows travel

with no shadow or trace on the road.

Loneliness dashes and smiles to the day

that climbs the hill

while the ants carry

their load silently.

————–

Those who search for beauty, find God.

————–

Have you ever heard flowers talking in the night?

Everything is full of secrets around us.

Even in a rock life is hidden

-nothing is dead.

————–

It is hard to tread on the earth without

having support in the clouds.

Only those who search discover the truth,

the treasure, themselves and other worlds.

————–

On hills, in forests, on meadows

the word of the soul is louder.

————–

Life is hidden in a rock,

dreamed of, but present.

Hit him, you will hear his heart beat.

————–

Light to everyone, everyone

until they notice the growth of a tree

in a grain

the beauty of a leaf on a thorn

and a brother in a worm

until they feel the brotherhood with

the bird, the wolf and the doe.

————–

Life without religion is like desert

swept by desert winds.

————–

What are you looking for – asks a flower –

Here, in the mist in front of the ruined house?

Even trees pray in the darkness.

Talk to me, wind, about the sun

On the plough-land.

————–

You who sit on the throne of the Secret

Unknown

Eternal

Mover of the world and the universe…

I am looking for you.

I wander through the spaces

of the centuries and worlds,

… and call your name all the time…

————–

Nature cleanses the man,

It fills him with power of the mind,

instinct and living forces,

And unveils the secret of modesty.

————–

Spirit is cleansed in the beauty of the nature,

it is being calmed,

it becomes wider and deeper.

————–

Stop and let me hear

the grass waking up

to the light

and offering itself to be kissed by the sun……

————–

He is silent

and he is lighting the stars

to shed light on the paths and ways,

tracks and roads

and minds

that lead to the Truth.

————–

On the Crown near my village

griffons nest

into the sky they dive

They circle

They fly up

and challenge the storms.

————–

I always come back to you, oh bella Libella,

difana snella

with no veil

as you fly like an arrow –

over a well

by the water, near the water

always in the light and

world of the freedom

twinkling, easy

woven from searays

Libella, si cara, si bella, sorella

A.V.M.

————–

Auf Deutsch:

Vermächtnis

Söhne habe ich nicht, noch habe ich Enkel.

Wem soll ich hinterlassen das Gedicht und den

Traum und die großen Flügel der Ahnung,

die über alle Grenzen reichen?

Dir, mein Volk!

Aus Dir bin ich hervorgegangen,

durch dich kehre ich zurück

in die Unsterblichkeit,

um weiter zu strömen durch den Untergrund,

um mit den Blumen auf den Feldern zu wuchern

und mit Tropfstein unter der Erde zu bauen

am Tempel der Schönheit und des Traums.

Alles Dir und nur Dir,

mein kroatisches Volk.

————————

Als ich in Beli ankahm,

war Finsternis.

Ställe voller ersterbender Klänge,

Schluchten und Schlachten voller Geister

und Gespänstergedränge,

das Meer voller Sterne und der Himmel

– voll von tiefem Geheimnis

und von unendlichem Blau.

————–

Vor der Wahrheit verneige dich,

an die Pforte des Geheimnisses kolpfe an und bitte!

—————

Es laufen Straßen und Träume und Leiden

ohne Schatten und ohne Spuren.

Die Einsamkeit eilt vorbei und lächelt dem

Tag zu, der sich den Berg hinaufwindet,

auch de Ameise trägt ihre Bürde ohne ein Wort.

————————-

Wer die Schönheit sucht, findet Gott.

————————–

Hast du jemals gehört das Gespräch

der Blumen in der Nacht?

Alles ist voller Geheimnis um uns herum.

Leben verbirgt sich auch in einem Stein

– nichts ist tot.

——————————–

Schwer ist’s die Erde zu betreten ohne Halt

in den Wolken.

Nur die Suchenden entdecken die Wahrheit,

die Schätze, sich selbst

und die Welten.

——————————-

Auf den Bergen, in den Wäldern

und auf den Wiesen hört sich

das Wort der Seele besser.

————————–

Auch im Stein verbirgt sich das Leben,

im Traum zwar, doch ist es da.

Klopfst du ihn,

hörst du sein Herz schlagen.

—————————–

Licht für alle, alle, bis sie erblicken

das Wachsen eines Baumes aus dem

Samen, die Schönheit eines Blattes auf

einem Dorn, den Bruder in einem Wurm,

und bis sie fühlen die Verwandtschaft

mit Vogel, Wolf, Reh…

————————–

Ein Leben ohne Glauben

ist wie ein Ödland,

über dem die Wüstenwinde wehen.

——————————

Was suchst du – fragt mich die Blume –

im Nebel vor den Häusern mit den zerfallenen Dächern?

Im Dunkeln beten auch die Bäume.

Erzähl mir, Wind, von der Sonne

auf dem Feld.

——————————

Du, der du sitzt

auf dem Thron des Geheimnisses,

unbekannt, ewig,

Beweger der Welt und des Universums…

Dich suche ich.

Ich wandere durch die Räume

der Zeiten und Welten

…und rufe immer nach Dir…

————————————

Die Natur läutert den Menschen,

erfüllt ihn mit der Stärke des Geistes,

des Instinkts und der Lebenskraft,

Und sie offenbart das Geheimnis

der Bescheidenheit.

———————————-

In der Schönheit der Natur reinigt sich der Geist,

kommt zur Ruhe und wird weiter und tiefer.

————————–

Warte, dass ich höre

wie das Gras erwacht

und dem Licht zuruft

und die Sonne um einen Kuss bittet…..

——————————-

Er hüllt sich in Schweigen

und entzündet die Sterne,

um zu beleuchten Pfade und Wege,

Landstraßen und Stege

und den Verstand,

der zur Wahrheit führt.

———————————-

Auf der Krone über meinem Dorf

bauen die Adler ihre Horste,

sie tauchen in den Himmel,

sie kreisen,

sie steigen empor

und trotzen den Stürmen…

——————————-

Immer kehre ich zurück zu dir, schöne Libelle,

durchsichtige Schnelle, ohne Schleier

fliegst du dahin wie ein Pfeil –

über die Quelle

auf dem Wasser, an dem Wasser,

immer leicht im Licht

und in der Welt der Freiheit

schwirrend,

wie ein Geflecht aus

Sonnenstrahlen.

Libella, du liebe, du schöne

Sorella.

A.V.M.

In italiano:

Testamento

Non ho figli ne nipoti.

A chi lascio la canzone ed il sogno

E grandi ali del Presentimento

Che salutano nell’infinito?

A te, popolo mio!

Da te ho germogliato,

Attraveso te, torno all’immortalità

Per scorrere poi nel sottosuolo

Crescendo poi con i fiori sui campi

E costruendo i stalagmiti nel sottosuolo

Per il tempio di sognante bellezza.

Tutto a Te e per Te

Popolo mio Croato.

——————-

Quando arrivai a Beli

Fu buio.

Le stalle piene di suoni morenti

I passi e valici pieni di spiriti e fantasmi

Il mare pieno di stelle

Ed il cielo

Pieno di segreto profondo

E di un infinito azzurro.

——————-

Inchìnati davanti alla verità

Bussa davanti alla porta del segreto e prega.

——————-

Viaggiano le vie ed i sogni e le tristezze

Senz’ombra etraccia sulla via.

Corre la solitudine e sorride al giorno

Che si arrampica sul monte

E le formiche portano i carichi

Zitte.

—————–

Chi cerca la bellezza, trova il Dio.

—————–

Hai mai sentito la conversazione dei fiori nella notte?

Attorno a noi ci sono tanti misteri.

La vita si nasconde anche nei sassi

– non e morto niente.

—————–

È diffidle calpestare Ia terra senza punto d’appoggio

Sulle nuvole

Soh i ricercatori scoprono Ia verita, il tesoro,

Se stessi ed il mondo.

—————–

Sui monti, nei boschi, sui prati

La parola dell’anima

si sente più fortemente.

—————–

La vita si nasconde anche nel sasso

Addormentata, ma è sempre Ii.

Dagli un colpo,

e sentirai il palpito del suo cuore.

—————-

La luce a tutti, a tutti

Finche non vedano la crescita dell’albero nel grano

La bellezza del foglio sulla spina

Il fratello nel verme

E sentano la fratellanza con l’uccello,

il lupo e

Il capriuolo.

—————-

La vita senza religione e come

il deserto su cui

Soffiano i venti del deserto.

—————-

Cosa stai cercando – mi chiede il fiore –

Nella nebbia davanti alle case dei tetti crollati?

Nel buio anche gli alberi pregano.

Raccontami, vento, del sole

Sul campo.

——————

Tu che stai seduto sul trono del Segreto

Ignoto

Eterno

Inizatore del mondo e dell’universo…

Ti sto cercando.

Vago per i vasti spazi dei secoli e

Dei mondi.

… e Ti chiamo sempre…

—————-

La natura purifica l’uomo

Gli da la forza dell’intelleto, istinto e

Le forze di vita

E svela il segreto della modestia.

—————–

Nella bellezza della natura lo spirito si purifica,

Si calma, e diventa più largo e profondo.

—————-

Fermati ch’io senta

Come si sveglia l’erba

E come riceve la luce

E come si offre al sole per esser baciata…

—————–

Lui tace

E accende le stelle

Per illuminare le vie e viuzze

I sentieri e le strade

Ed anche le menti

Che guidano verso la verità.

—————–

A Kruna vicino al mio villaggio

Le aquile si annidano

Scoscendono in cielo

Girano

Prendono il volo

E affrontano le tempeste

——————-

Ritorno sempre a te, o bella Libella,

Difana snella

Senza velo

Mentre voli come una freccia-

Sopra la fonte

Vicino all’acqua, lungo l’acqua

Sempre alla luce e nell mondo

della libertà

Tremolante, leggiera

Intrecciata dai raggi di sole

Libella, sì cara, sì bella, sorella

A.V.M.