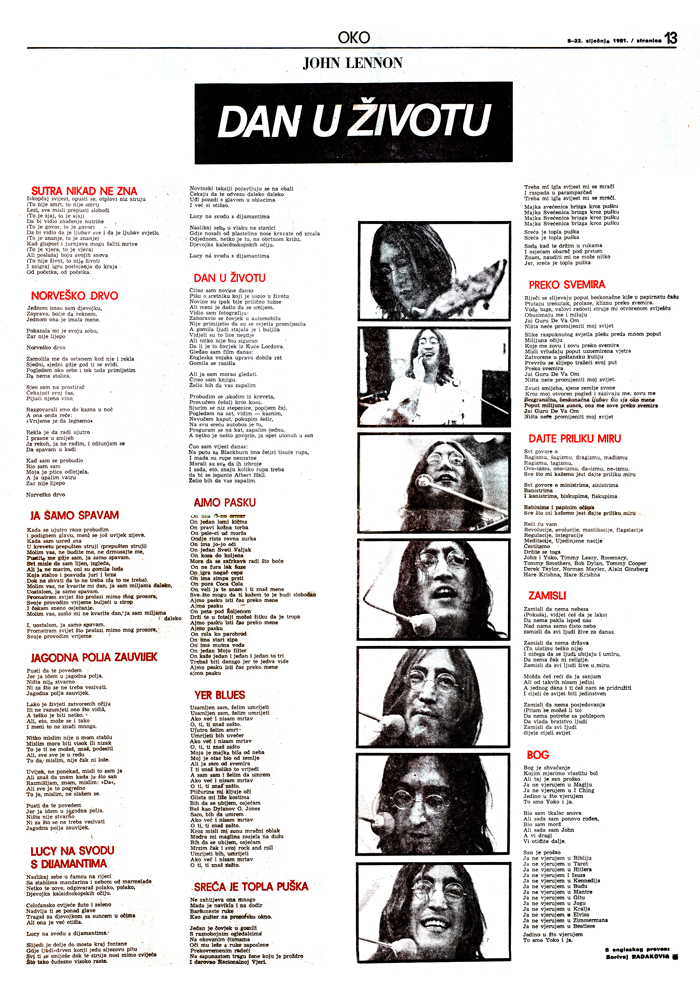

Tag Archives: yugoslavia

Protected: John Lennon Hilton Amsterdam 1969 interview in English – part 2

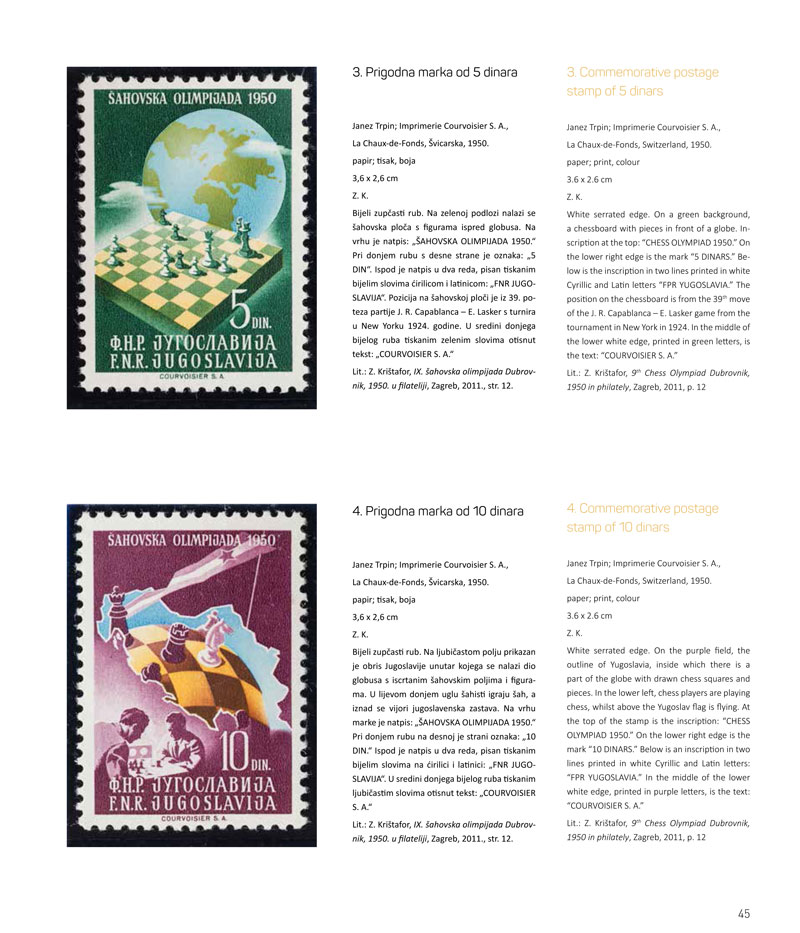

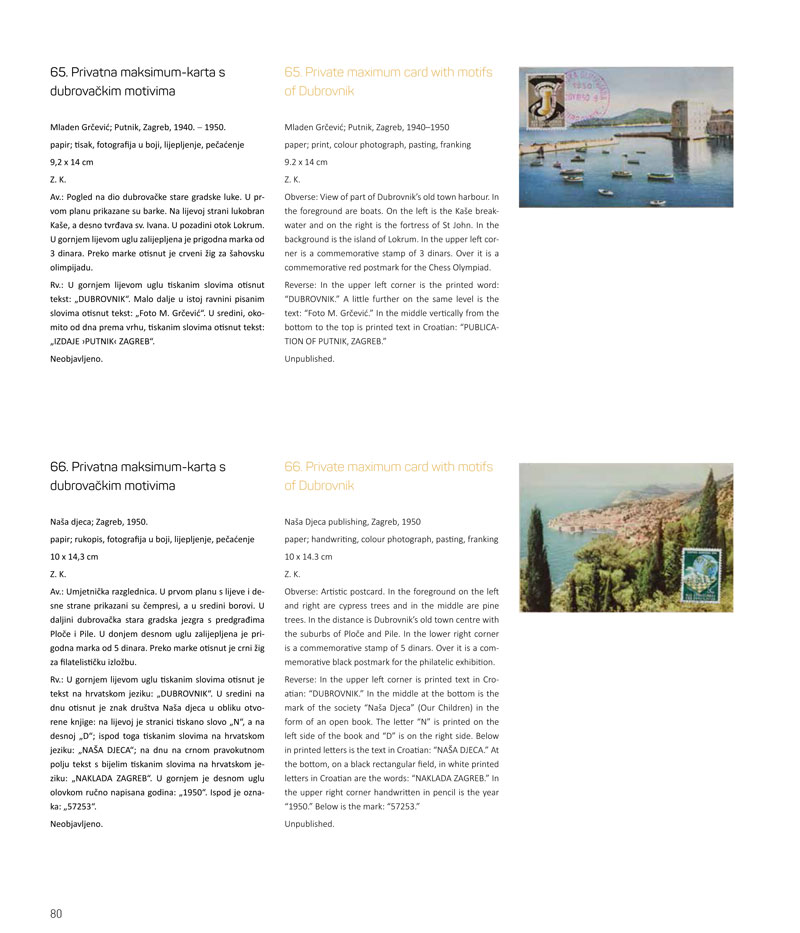

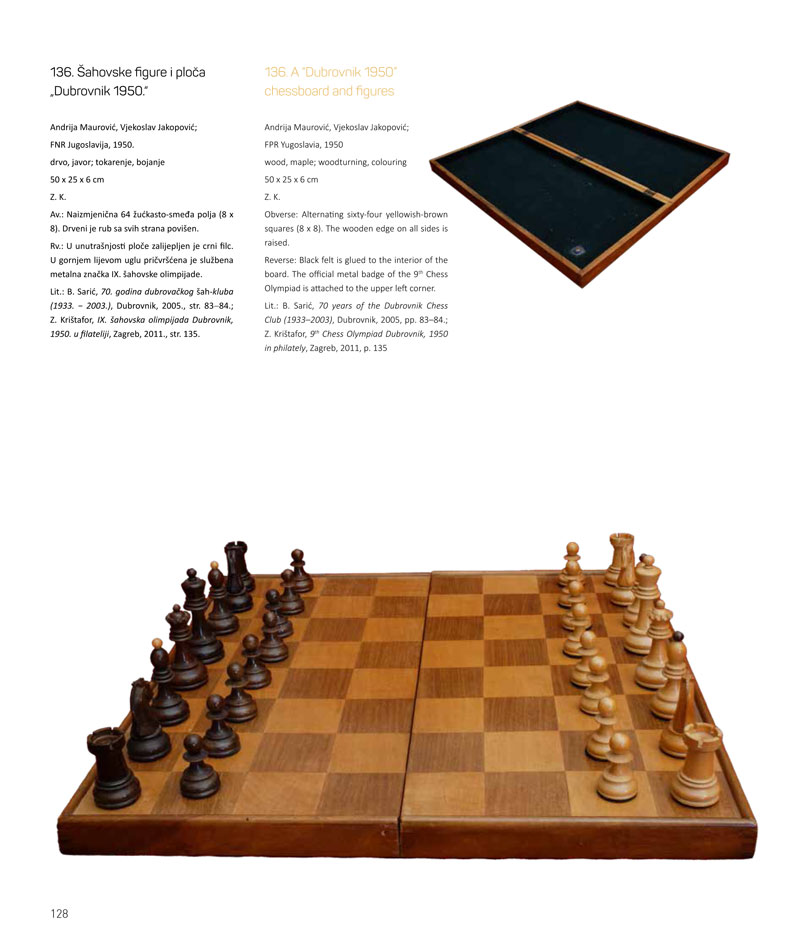

Chess Olympiad commemorative catalogue

The 9th Chess Olympiad – Nations Tournament of 1950 was held in Dubrovnik, Croatia in 1950 and the team of the hosting country – FPR Yugoslavia – won. This catalogue of the exhibition published by Dubrovnik Museums commemorates this special occasion in the history of chess.

The book features the whole story of the competition, the competitors, the ceremonies and the results. The highlight of this edition is the catalogue section of the postage stamps, first day covers, postcards, posters, chess sets – the Dubrovnik set later became a standard – and much more that were issued during and after the tournament.

As the English translator for the catalogue it was especially interesting to learn about the event and particularly about the philately part because I was an avid stamp collector as a schoolboy 🙂

The authors of the text are Tonko Marunčić and Zdenko Krištafor.

You can follow Dubrovnik Museums on Facebook here

…. there is more info about the tournament here.

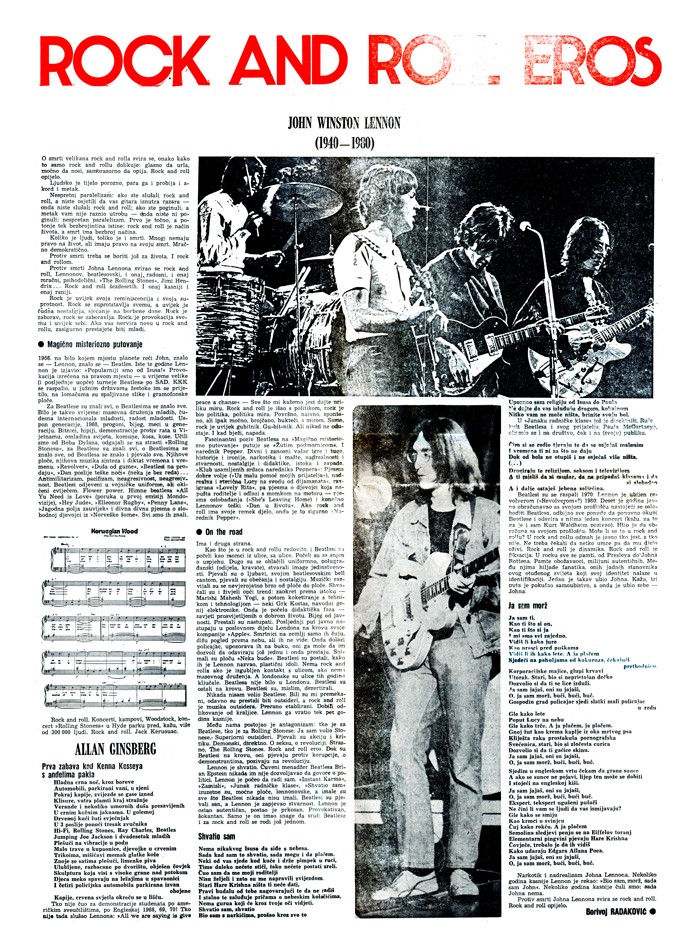

Protected: The Beatles – report from Abbey Road 1967

Protected: John Lennon – lost 1971 interview

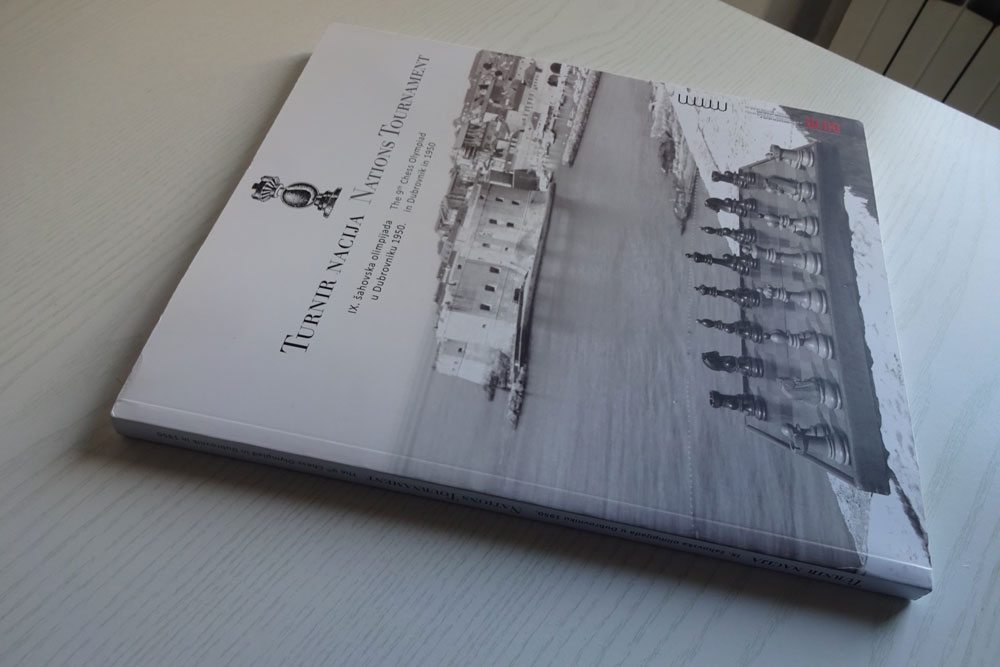

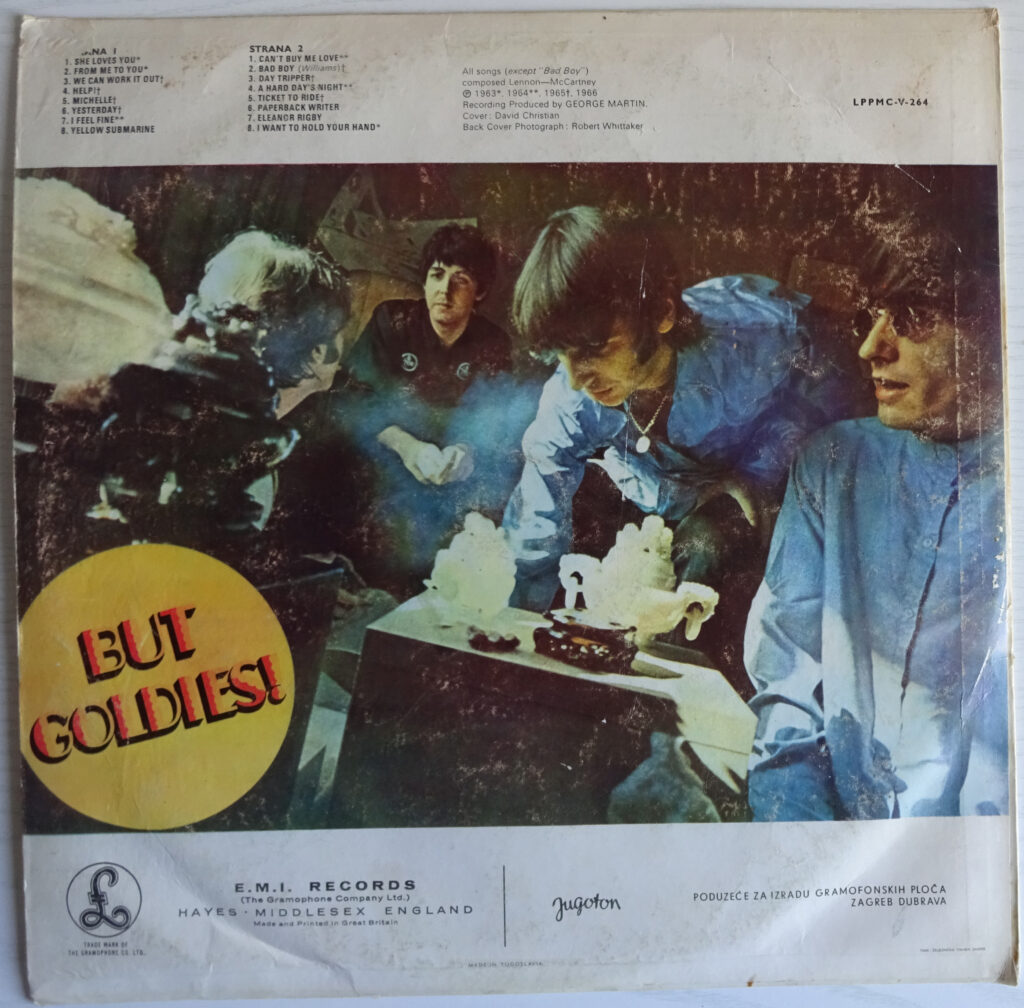

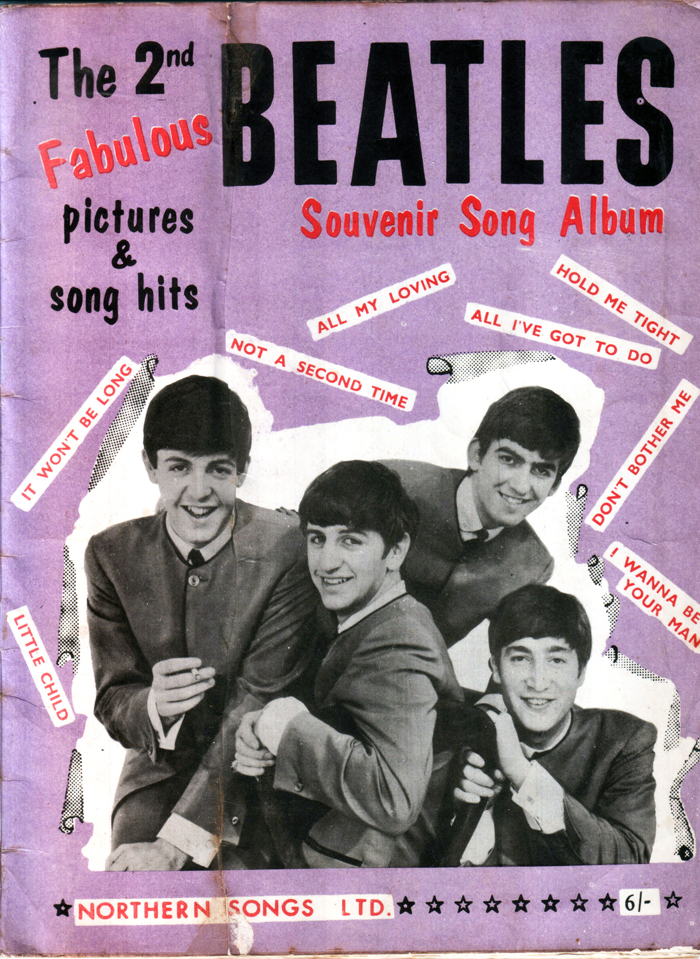

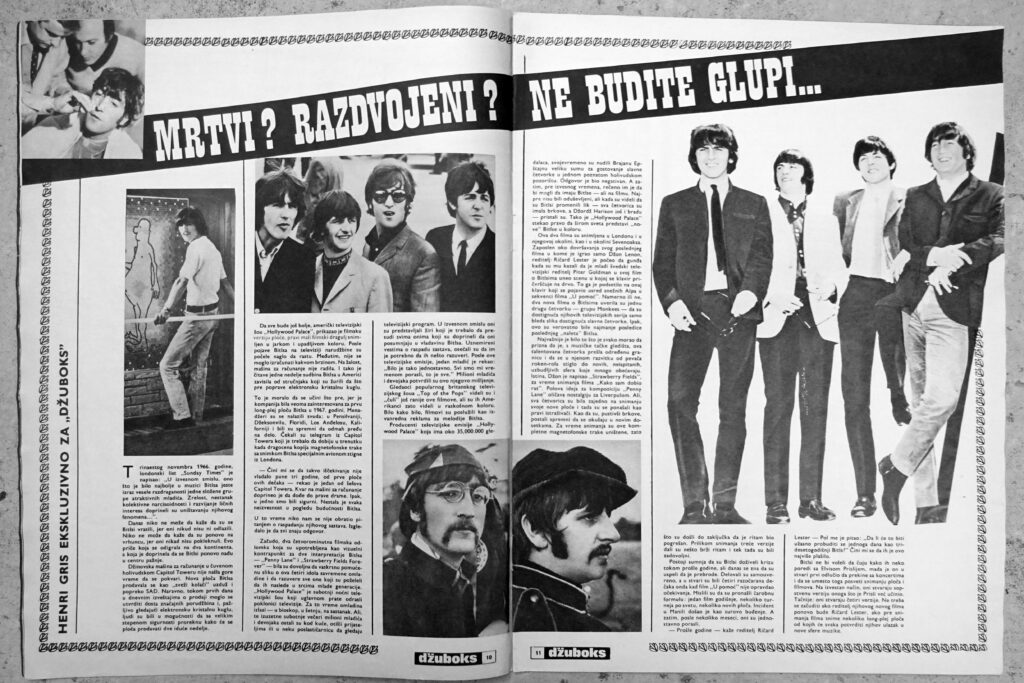

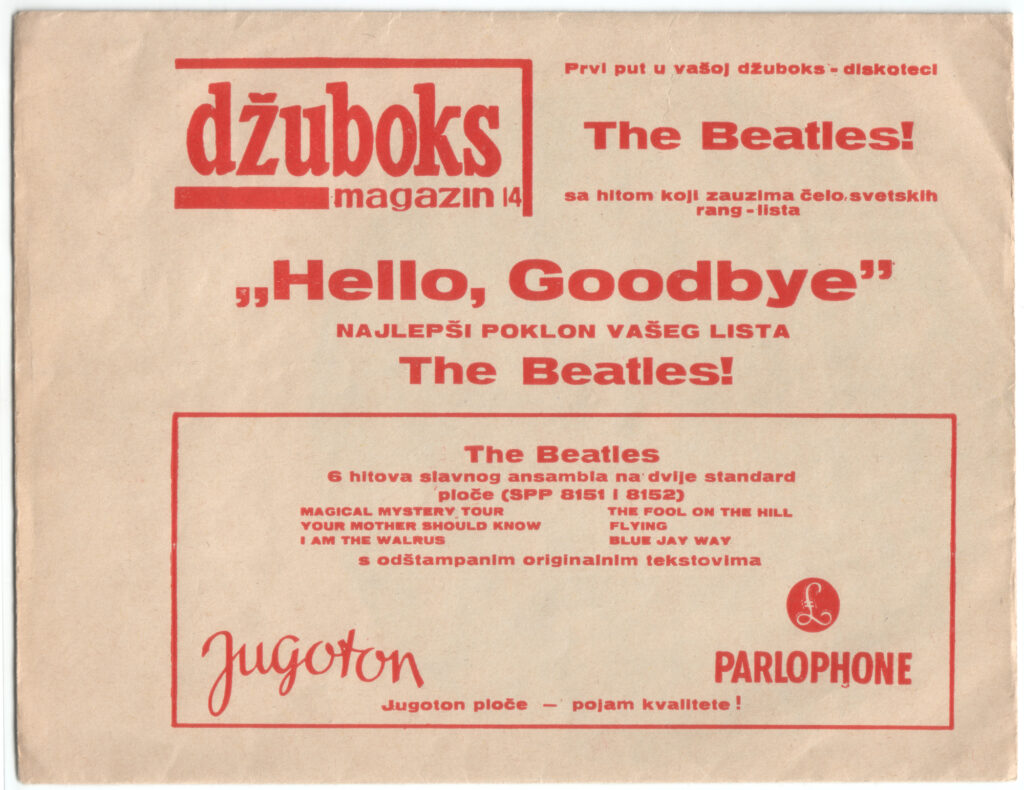

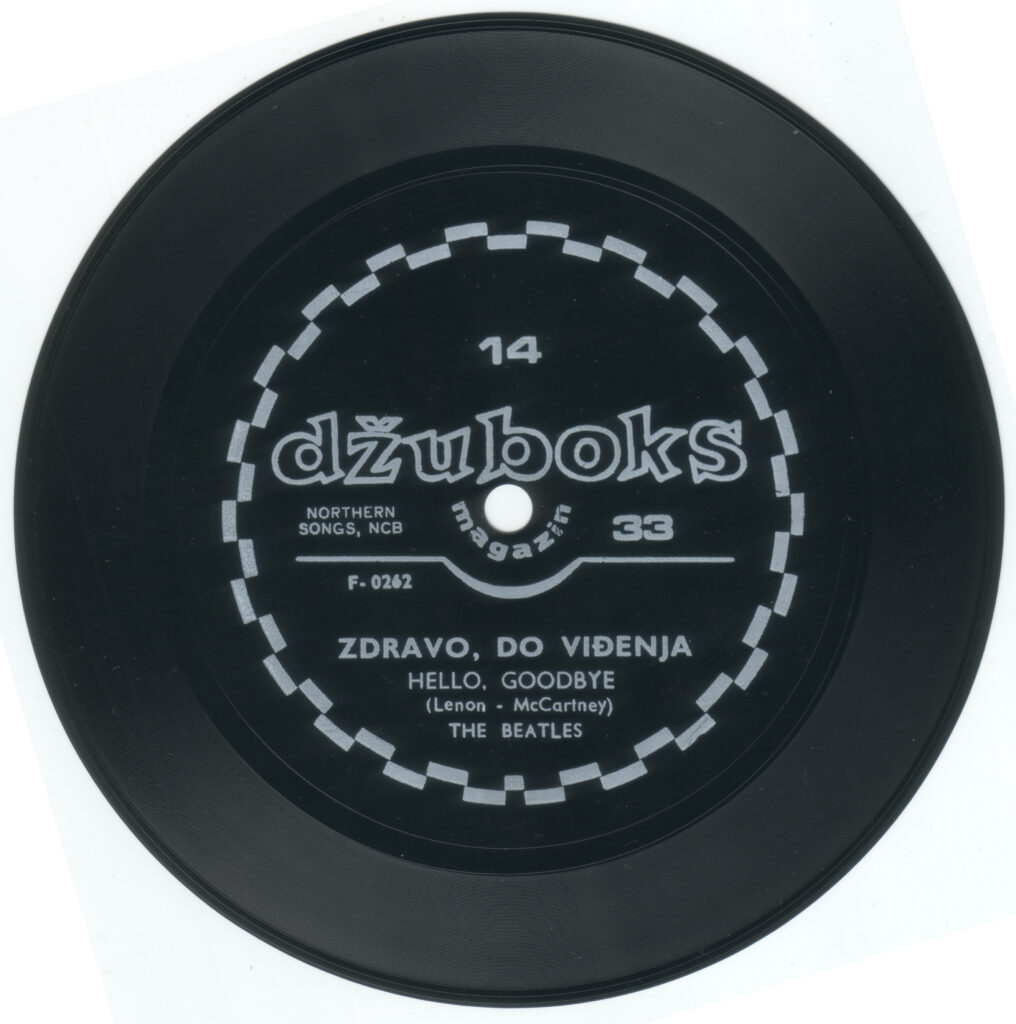

The Beatles memorabilia

I’ve been a Beatles fan since I was a boy. I’m always delighted to find Beatles memorabilia here in Croatia. Here are a couple of things I’ve found in Rijeka.

Thank you Tomo @ Antikvarijat Mali Neboder, Rijeka

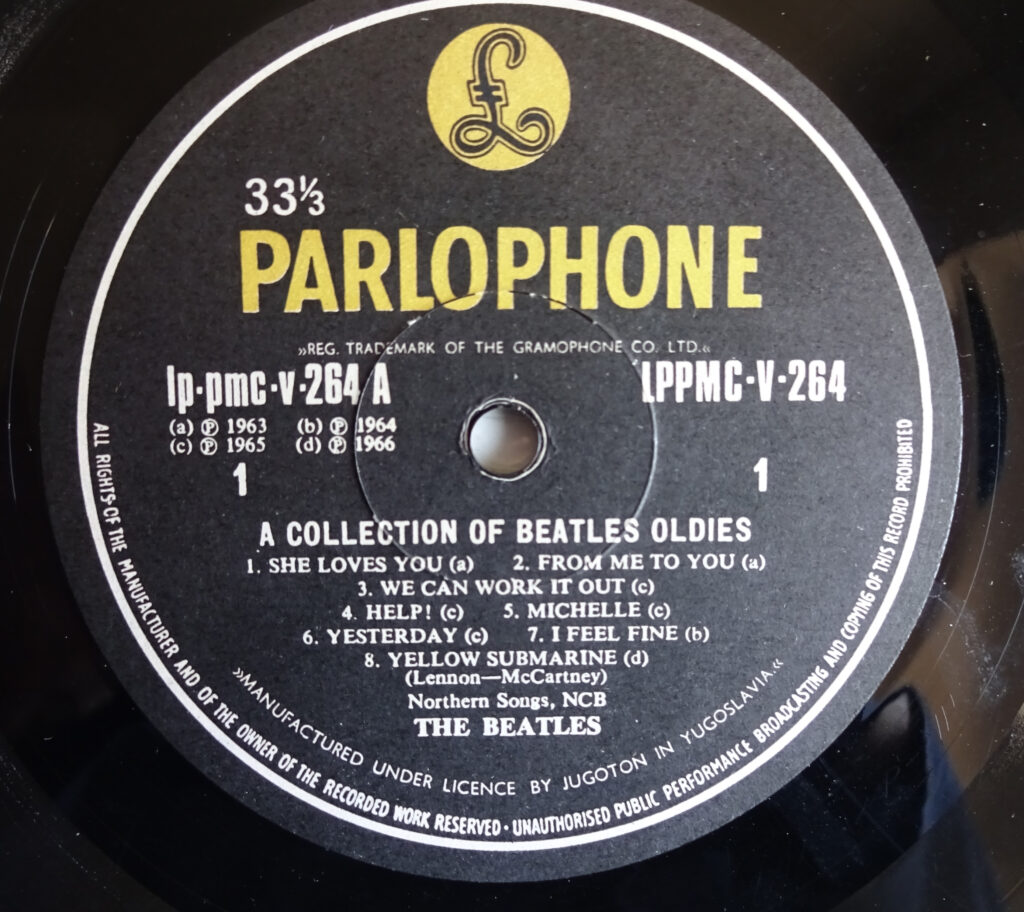

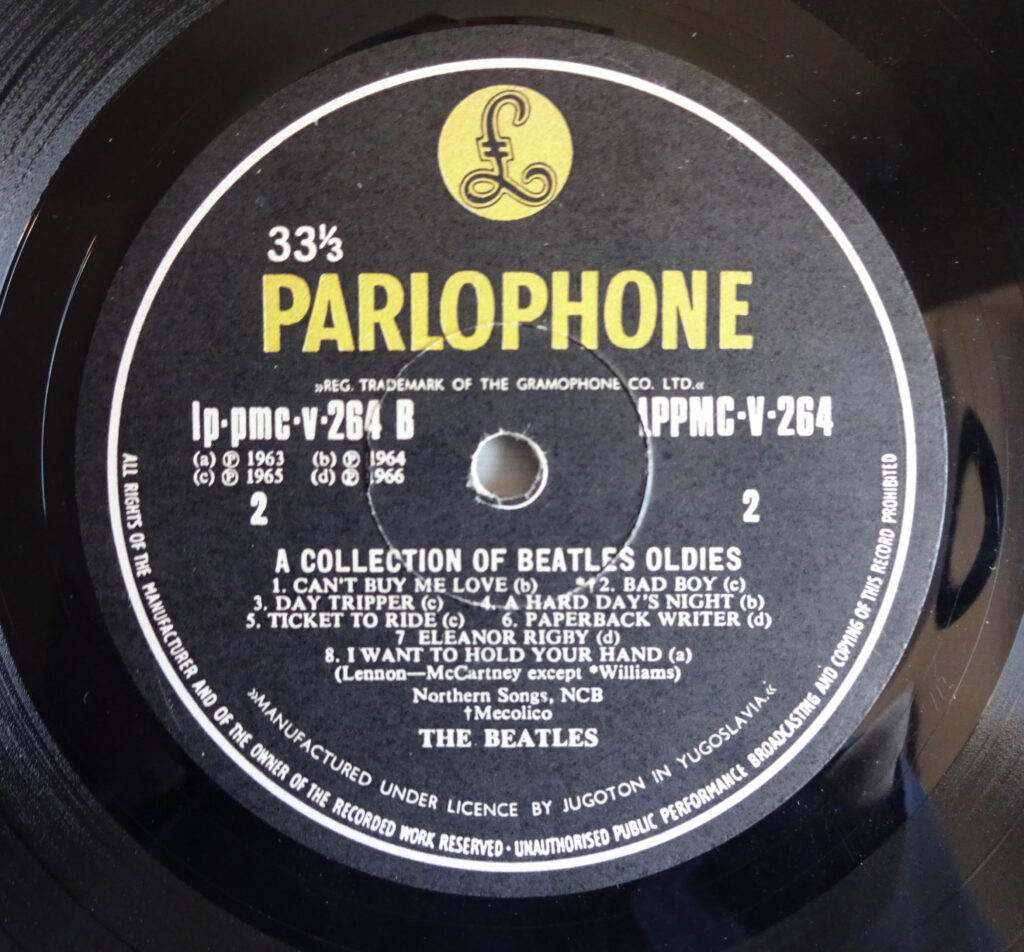

Interesting that this issue has a different name to the rest of world although the labels are A Collection of Beatles Oldies. Catalogue number: LPPMC-V-264.

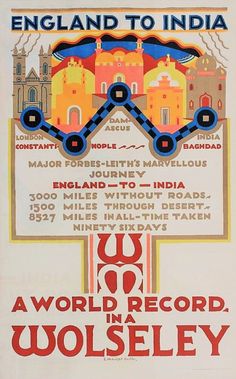

England to India by automobile, via Fiume in 1924

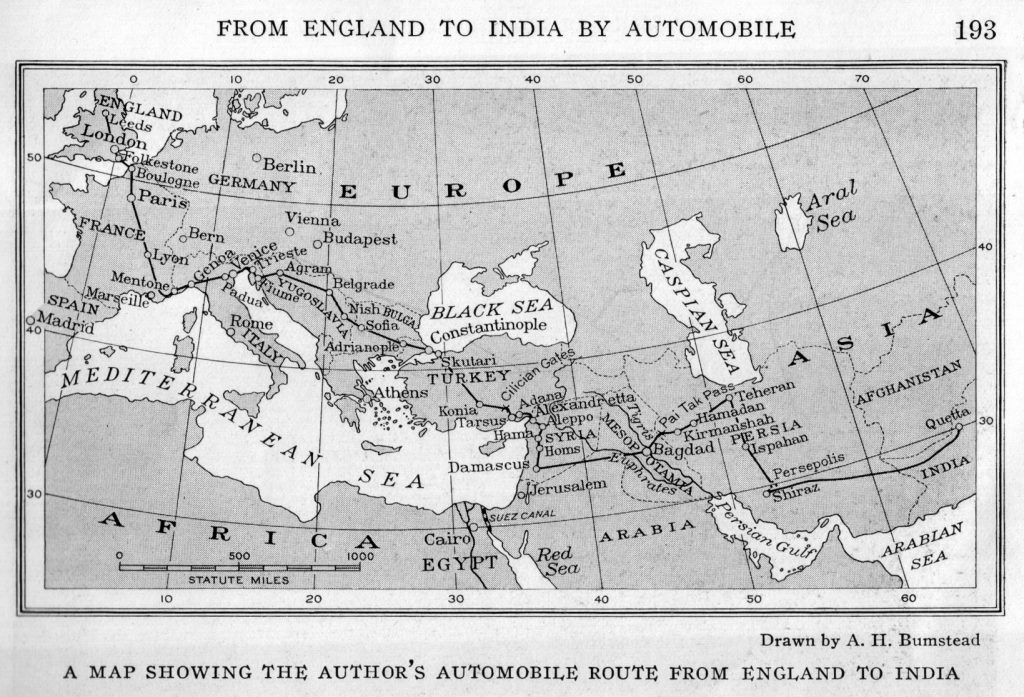

FROM ENGLAND TO INDIA BY AUTOMOBILE

An 8,527-mile Trip Through Ten Countries, from London to Quetta, Requires Five and a Half Months

BY MAJOR F.A.C. FORBES-LEITH

extract: THE FIUME “LIONS” OF ITALY’S POET SOLDIER

extract: THE FIUME “LIONS” OF ITALY’S POET SOLDIER

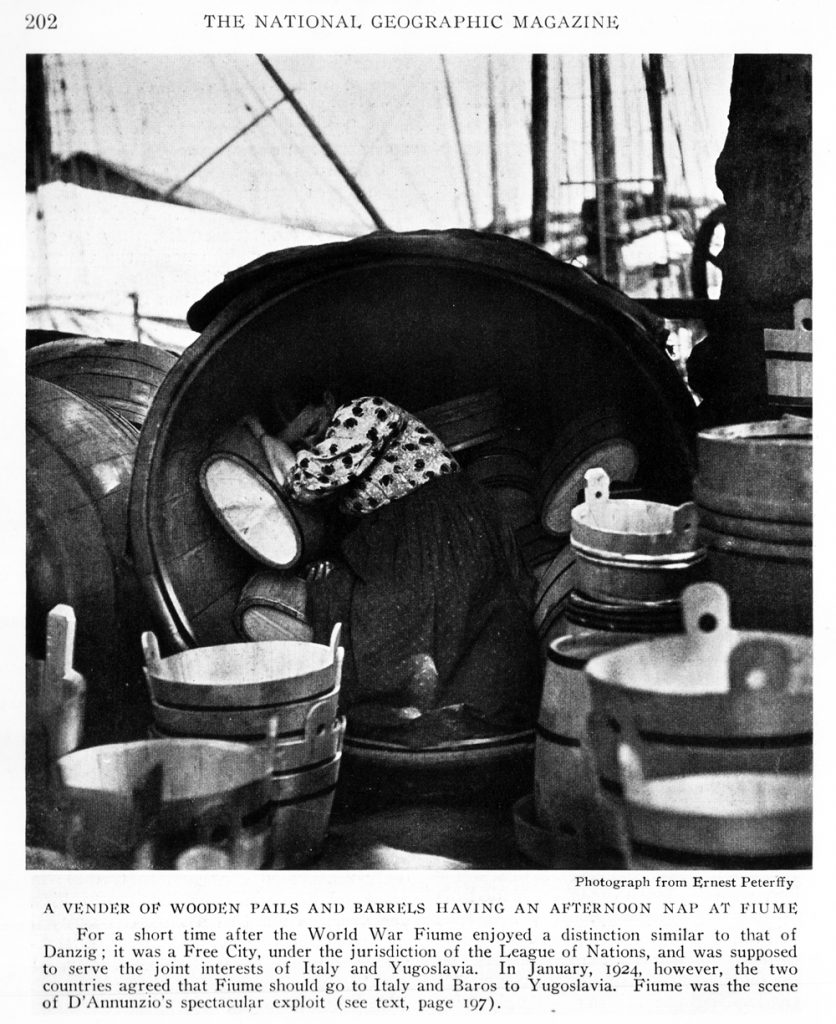

Our next stop was at Fiume (Rijeka), the scene of the coup of Gabriele d’Annunzio, Italy’s poet patriot. It is also a fine port, but a mean city in comparison with Trieste. A narrow river separates it from Susak, the Yugoslavian frontier town.

An impressive sight in the city was the great number of apparently idle young men with shock heads of hair fluffed out like a lion’s mane. We thought this must be the latest thing in Fiume masculine styles until an English-speaking friend explained that this is the hall mark of d’Annunzio’s “lions,” who, with him, captured the city.

We were warned not to upset any of them, as they have the reputation of being excessively irascible and a law unto themselves.

After a night in Fiume, we crossed the frontier bridge to Yugoslavia. The incredible change made by those few yards is impossible to imagine – a jump from stagnation and slackness to hurry and bustle.

The only place into which the general energy had not penetrated was the customhouse. We had a letter of introduction to the chief revenue officer, who told us that, as a great favour, they would rush us through the formalities. The “rush” required six hours to deal with our small outfit!

The only place into which the general energy had not penetrated was the customhouse. We had a letter of introduction to the chief revenue officer, who told us that, as a great favour, they would rush us through the formalities. The “rush” required six hours to deal with our small outfit!

The officials seemed to like our company. As soon as the papers were passed to a fresh clerk, he would come and have a friendly chat with us on European politics, our trip, and, in fact, anything but the business concerned. They were so cheery and genial that we could not take offense; so we smoked endless cigarettes and waited.

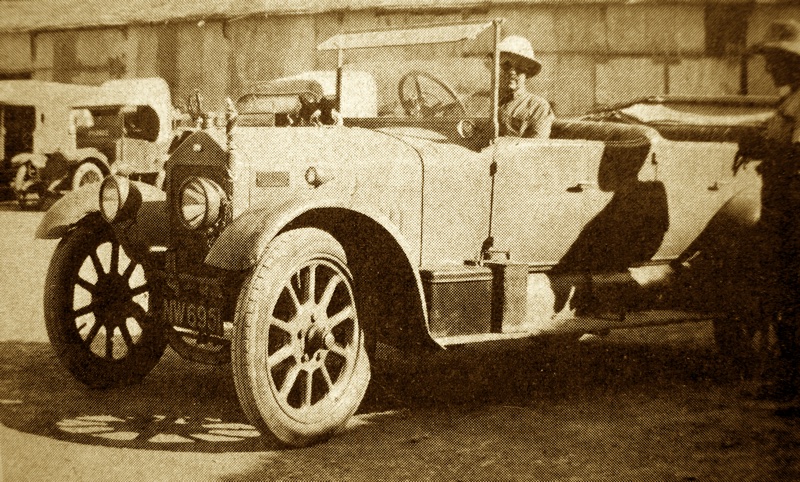

Overland from England to India in late 1924 by Major Forbes-Leith. Here seen in Baghdad on 20th August 1924.

EVERY VILLAGE CAFE IN YUGOSLAVIA HAS ITS ORCHESTRA

We were now in a new kingdom, a charming country of delightful, music-loving people. Every little village café has its orchestra of young men playing the guitar and mandolin, and accompanied by a trio or quartette of girl singers. The former stand and play; the latter sit in a row in front and sing national songs from dusk to midnight.

The Croats and Serbs are fine fellows of good physique, very hard workers, great patriots, and among the finest soldiers in the world. Serbia, before the World War, was spoken of as a little Balkan state; now she must be reckoned as a power in Europe.

At Agram (Zagreb), the capital of Croatia, formerly part of the old Austrian Empire, we had a shock that made us rub our eyes. In front of us at the first crossroad, was the embodiment of an English policeman, with helmet, uniform, and baton complete. We heard afterward that the whole police force of the city was modeled and trained on British lines, even uniforms being supplied by outfitters in England.

In atmosphere, architecture, and general plan, Agram is a miniature Vienna. It has a fine opera house, and the architecture is for the most part typically Austrian.

Living is very cheap here for the man who carries either the pound sterling or the dollar.

*******

The trip was made in 1924 and published by The National Geographic Magazine August 1925.

There was even a cameraman on the trip and there exists footage – called ‘Lure of the East’ of some of the trip available here on the British Pathe archives website. And on Vimeo – watch at 1:00 and you’ll see a Zagreb copper: https://vimeo.com/45439980

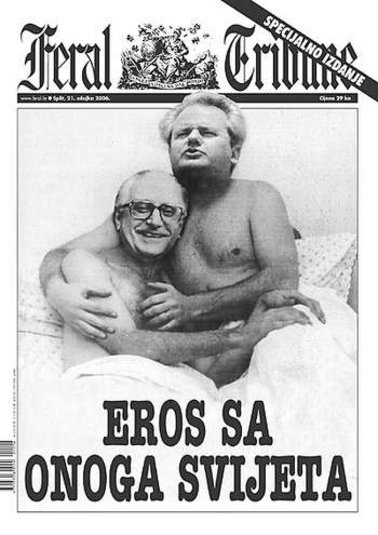

Feral Tribune – book summary

The book ‘Smijeh slobode – uvod u Feral Tribune’ (‘The Laughter of Freedom – an introduction to the Feral Tribune’) by Boris Pavelić describes and explains the 25 year old cult political-satirical newspaper the ‘Feral Tribune’, based in Split. It was published from 1983-2008 in various forms and billed itself as a “weekly magazine for Croatian anarchists, protesters and heretics.”

The book ‘Smijeh slobode – uvod u Feral Tribune’ (‘The Laughter of Freedom – an introduction to the Feral Tribune’) by Boris Pavelić describes and explains the 25 year old cult political-satirical newspaper the ‘Feral Tribune’, based in Split. It was published from 1983-2008 in various forms and billed itself as a “weekly magazine for Croatian anarchists, protesters and heretics.”

The publication won international awards in the 1990s but slowly went out of circulation – this book studies the history and value that it had and still has in modern-day journalism.

The book is only available in Croatian and I translated the summary into English. It is hardback, has 688 pages and its ISBN: 978-953-219-492-0.

It is published by Adamić d.o.o. and is available in shops and via the publisher’s website here: http://shop.adamic.hr/index.php

Antun Barac – ‘Fiume’ in English

‘Fiume’

(passing impressions, July 1919)

by Antun Barac – translated for the first time by Martin Mayhew

Three beautiful, sunny, autumnal days. I don’t know what happened. In a single morning all the ties snapped, that were holding the voice in the throat, that loosened the links, that were chaining the feet, the heavy and rigid mask fell, that was hiding the face. A quiet whisper, which spoke curses and revealed a howl, scattered itself like a wild, holy cry of joy, whilst a hand, a pathetic hand, taught to give a servile and official greeting, extended for the first time in a bold gesture of belief and confidence in itself.

We went onto the streets, in processions, assemblies, groups and we sang and cheered. And everything was so sunny, bright and light. And everything was clear and cheerful and happy in the beautiful, clear autumnal day.

In the barracks there were soldiers, and they were cheering. In the hospitals there were wounded, and they were singing. The soldiers came out onto the streets and were firing their guns. After four blurry years it was the first time that the firing meant joy, after four sombre summers it was the first time that a bullet didn’t mean death, but life. And it was as though that shot, which was now rising into the air, was a symbol, as it rises and as it falls.

On the chests flowers and tricolours. In the windows flowers and tricolours. On the streetlamps, on the telephone poles, on the makeshift stands flowers and tricolours.

In a red, white, blue, green colour, in the grey colours of joy, ecstasy, hope and belief, on each flag, that flutters, of elation, love, sympathy and adoration, which the flag as a symbol means. In the red glow of love and brotherhood towards everything and everyone, in the whiteness of the cleanliness and sublimeness of ecstasy, hope in the new world, that was being created.

We went out onto the streets and sang. We welcomed the foreign troops and sang. We threw flowers and sang. We welcomed ships from foreign countries and sang. “Call out, just call out… Viva la France! Allons enfants de la Patrie!…” And the children of the homeland arrived, and laughed, and danced, and cheered.

“Here people just walk around and cheer and sing” – they say, wrote home one French sailor. “Viva la Yugoslavie!” His compatriots cheered – and in their scepticism and in their laughter for the sake of laughing and joy for the sake of joy we felt the first stab of disappointment and misunderstanding.

In an isolated corner an old hunched over woman was sobbing. “Woman, why are you crying?” – asked a voice – I don’t know whose, and I don’t know where from. “In every joy there is a note of pain, in every laugh a seed of sorrow”, as though replying to somebody’s voice – who knows whose, who knows where from?

Three beautiful, clear, sunny, autumnal days. Three days of song and clamour and ecstasy. And then – armoured cars, machine guns and horses on the cobblestones and pikes, stretching up high, rigidly, arrogantly. In the port heavy ships with cannons aimed at the city, on the street assault troops with helmets, rifles, knapsacks and ammunition belts.

Three beautiful, clear, sunny, days passed. And nothing to show for them. Only a difficult, long winter with clouds. Just a cold summer with raindrops, that with the ‘bura’ and rain even the tears froze. Just a gloomy spring without light or sun.

Maybe a time will come, when all the ecstasy and elation will seem ridiculous to us. Maybe a period will come, when every sense will be reduced to a mathematical or chemical formula. I only know, that even then, when I was in the height of national fervour, I felt no desire for revenge or hatred or malice – the days of the greatest joy were days of forgiveness for everything, to all who had oppressed us, days of national liberty, a time when love for everyone was the most lively, the most conscious. And in those days of intoxicated delight and love, that had boiled over, the clenched fists, clashes and attacks were the end of everything.

I don’t know what happened. In just one day with a wild roar they began to tear down the tricolours of red and white and blue, and in the windows, on the streetlamps, the houses, the buildings, the churches suddenly others appeared – red and white and green, with a star and a coat of arms. Everywhere the coat of arms and everywhere the star, and everywhere fanatic hatred in the faces and fury and poison in the looks. “Italia o morte! Fuori il straniero!” Whilst the straniero thoughtfully stops and thinks: “Who in fact is the stranger?”

In these sombre days of waiting and incertitude, desperation and zeal, it is so difficult to be alive and carry all the heavy burden of the present; however it is hardest to be human. So many times I have felt the pain and burden of life, but the worst thing was when I felt the aching shame, I didn’t feel fear for myself, but for those who persecuted us, the shame of man, that chaotic, disproportionate mixture of beast and god. The beast, wild, brutal, vicious, kicking and rearing up, and the god, sublime, the ashen sceptic levelling with it, taming or incensing it. And in the battle of animal with god like the battle of a bull with a toreador – the white, red, blue, green colours, that they have signifying a symbol, they stimulate it, intoxicate it, they extol it, bring it to an ecstasy of madness and rage. Fiume, the yellowish-grey, deceitful animal, from the eyes of which peer the envy and intoxication of excessive enthusiasm, throws itself, snapping, howling and moaning into exhaustion, until it falls bewildered, unconscious to the ground.

Therein the roar is so quiet! Therein the crowd is so uneasy and lonely. In this racket our steps reverberate so eerily. Oh, the whole of this city, whose number of inhabitants doubled in a few months, as it turned into a huge, grey, isolated monastery, where the shadows succumb to the wolf, hollow songs reverberate and the voices of muffled prayers drone. And thus it is miraculously quiet and in the murmur, so terribly calm in the constant throng.

Why call this city Rieka, when it is – Fiume. Reka, Rika, Rieka – that sounds so sweet, placid and childlike like the nostalgic “ca” and “ča” of the people of Drenova, Plase, Trsat, reminiscent of the sunny gleam of the stone walls and enclosures scattered with rocks and brambles, amongst which, in spring, blossom such beautiful and fragrant violas, a modest and shy flower. It is a city with a filthy physiognomy and with an inner self bland and murky, like the murky Fiumare canal, the dead water that cries for it. The Fiuman is a separate race, not belonging to any one nation. It is a mixture of everything that has come to this merchant city to trade – of everything, of many things. The Fiuman is both an Italian and a Yugoslav – an Italian, born of Yugoslavs and brought up as a Yugoslav, who cheers at the top of his voice: “O Italia o morte!”, the Yugoslav is a quiet and timid beast, hiding because of his interests of his national origin with a neutral, inexpressible, merchant’s sneer. Whilst the Riečanin, Recan, Ričanin – they are the masses – they are the nameless mass, who don’t ask, quantité négligeable, they are the inhabitants of the workers’ houses, basements and attics, the servants and labourers, small artisans and assistants, the masses, who have only one head, and who would, maybe, with just a single blow fall. And that is the characteristic, external image of the city – Fiume, Fiuman. And in this fatal exchange is the source of all the illusions, all the efforts and all the miserable disappointments.

Years and years of timid and quivering yearnings for the city of Kvarner and in that name I will stop with everything, that was the dearest and utmost in life – but then the bloody realisation, that it was all just a yearning for childhood, for the sea, for the days that had gone forever. Yet there is no city, there is no childhood and there is no sea. There is only Fiume and Gomila and Fiumara – a murky, stagnant mire, like a feeble residue of exacerbated human passions, without the strength that it vanishes, without the strength that it stirs up, rises, moves.

Corso. An evening stroll. In the looks a glow and depth, in the gestures a yearning and yielding to love. Yet the whole city seems to shiver from one single deep gaze, which rises from the bottom of the soul and seeps into the bottom of the soul, and the whole city seems to twinkle from love, that is only the soul, only the soul. Whilst down, in the depths, inside – ah, there is no soul and there is nothing, the base and desolation and emptiness. And the whole of this city and all these people who rousingly speak and shout and wave – the whole of this city has no soul, and everything, that moves it, is the basic animal life. And its voice is not the sublimeness of ecstasy nor the size of reproach – everything is just a roar, clamour and mania. And the moment will come and everything will boil over and everything will disappear, what froths up and what rises up – on the empty bottom will remain just Fiume, a city without a soul and without physiognomy and a notion without features.

Over five bloody years ten times in the memory of the sparseness and irritation of the nerves the city howled and ten times they changed the inscriptions and ten times in a fanatical irritation the masses passed over their old idols. Today on the ruins of everything, a fiery rage triumphs in the proud satisfaction, that with the greatest lie it refuted thousands of its little lies and that in the deafening cry it suppressed everything, that protests, that rebels. Because that cry is not a lie, because this fire of enthusiasm isn’t hypocrisy. It is Fiume and everything is Fiume. And to whomsoever this Città di San Vito belongs; whosoever flag will flutter next to the double-headed eagle with the yellow-blue symbol – will win, I’m afraid of Fiume, and with a shout of honest enthusiasm the malicious cry of a lazy and cunning animal will intervene. And that is my fear and it will be a drop of bitterness in that moment, which we will surely never live to see.

What can enthral a man in this city, in which culture and supremacy are denoted by the black marks on the walls and the holes in broken inscribed tiles? In our weakness for it there is a weakness towards one’s own past, which is contained in these pavements, street corners and quays, a weakness towards the whistle of departing steamships and the whiteness of unfurled sails, that awoke our childlike imagination and tied it to this place, that doesn’t love us. In our trepidation towards its destiny there is only the fear for those miserable, unknown, oppressed thousands, who just silently accept the blows and ridicule and the stamp of inferiority. We understand that the sinful must repent the sins and perform penance those, who have deserved it. However what did the little pale children commit that they must suppress their voices in their throats, the only one with which they are able to express the feeling of happiness in the joy and drive of wickedness in the game?

Our feeling of attachment with this city isn’t a feeling of love, but a feeling of pain, and fear, and hopelessness in the sense of a wounded animal and disgust and revulsion. Because it is just Fiume – and Fiume is not an organism, not a concept, not a soul, but something colourless and tepid and tensile, that with its odour tears at the nostrils and throat, and intoxicates and commits evil. And here nothing enthrals and here nothing is attractive. The love of this city – ah, it is an illusion, it isn’t love, but an escape from it, an escape to the blueness of the sea, the sigh of Trsat, the greenery of Opatija and Volosko and the serene vistas towards Kostrena, Omišalj, Cres and Ika. Everything that nature has warm and soothing and soft, is gathered around this city, to shield it, to protect it, to conceal it. And the reason why its poison didn’t act. In the moment when the heavy shackles fall from the chests and from the legs and from the hands and from the tongues, from all sides pale children will rush and shower it with flowers of love, forgiveness and it will forget all the insults, all the blows and all the threats.

From Školjić to Kantrida – one and the same street and one and the same image: houses without expression, without style, stores, shop windows, markets. In the place where there is only trade, all the houses are built on clear commercial principles: with the least expenses – the highest rents. Houses without physiognomy, without souls. In the city, where everything is measured purely in monetary measures, the friars had also taken advantage of the few metres of free space around the church and built umpteen little rooms for shops. Trade is not permitted in the temple, however it is better in front of and around the temple. The city of fifty thousand inhabitants did not give up one single man, whose name would be recorded in the history of culture and art, and wishing to somehow christen their streets, the fathers of the city were having to reach back for names from the mother countries: of Hungary and Italy. In a city of fifty thousand souls there is not one monument, and the only highpoints on the streets are advertising posts and lavatories – as unintentional symbols of it, as if it is the only purpose in this place. I love and appreciate trade as a means, but as soon as it becomes the meaning of life, it becomes both the negation and profanation of all higher values. And that which people would have to make them happy, to lead them ever upwards, throws them ever lower. And Fiume is deep, so deep.

Amongst its great evidence for being Italian the supremacy of Italian culture is prominent in Rijeka, the culture of the Italian is greater than that of the Yugoslav. Whilst the first glance at this city shows that it has, in general, no culture, not only of its own, but no culture of any kind, and that, which in the moment could deceive the eyes, is just glued on, that is easily washed-off by the rain or over night, when the city’s new generation is over-patriotically disposed.

The fun fairs, public houses, buffet bars, cafés, cinemas. All dirty, all abandoned, all in disarray. The dirt of the port as though it passes into the city itself, into every corner, every alleyway. This relatively large city is not capable of supporting a permanent theatre, whilst the companies, which are hosted here for a month, twice a year, can only be supported by the subscriptions of Yugoslav misers. In the place, where all the sights are just negative assets, such are the values and the two most important characteristics: Rijeka’s Gomila and Rijeka’s street gangs. The heart, the centre of the city, consisting of ancient ruins, disgusting mansions with narrow and winding streets, where the sun never reaches and where streams of undignified liquids flow freely; dangerous, dark corners, smelly inns, and women, and beggars, and drunks. While Rijeka’s street gangs they are a mighty gutter army, an abandoned mob that attacks the schiavi, that fights selflessly and fervidly for the lofty goals of the city’s fathers and less selflessly, for the needs of life. And that is – Fiume.

In the days of liberty, in the days of the universal love of forgiveness, a grey monster howled, that calls itself Fiume, with a howl of hatred and revenge. In the days, when kisses and expressions of brotherhood should have rained down, it prepared itself for secretive bites, punches and stabs. And why wasn’t the punch stronger, that is just the deceitful cunningness and feeling of weakness alongside all the abundance of gesticulation.

Is this city ours? Ours are those thousands and thousands of silent beings, who resignedly just wait, eternally waiting, thousands unarmed and unlawful, who upon the punch and the bite correspond with a speechless look, who upon an energetic nod from their masters sign up dutifully and without opposition, not asking: “Where to?” – It doesn’t matter, what they’re called. In the ascertainment of their anguish there was the justification of a love for them, from their speechless mouths comes a call for resistance, for rebellion, for liberation. And that is why, as their national consciousness is not strong, as the term of Yugoslavism has not developed in them yet, their pain is even stronger: it is the consciousness, that despises them, that brands them without reason, without cause, that they oppress the concept of man in them. Yet theirs is the main feeling, the feeling of shame, that they belong to a common creed unlawful, powerless, weak – and with the sense of the joy of life is mixed some dreary feeling of their own inferiority, a state of neglect before the mighty.

Is this city ours? Ours are those thousands and thousands of silent beings, who resignedly just wait, eternally waiting, thousands unarmed and unlawful, who upon the punch and the bite correspond with a speechless look, who upon an energetic nod from their masters sign up dutifully and without opposition, not asking: “Where to?” – It doesn’t matter, what they’re called. In the ascertainment of their anguish there was the justification of a love for them, from their speechless mouths comes a call for resistance, for rebellion, for liberation. And that is why, as their national consciousness is not strong, as the term of Yugoslavism has not developed in them yet, their pain is even stronger: it is the consciousness, that despises them, that brands them without reason, without cause, that they oppress the concept of man in them. Yet theirs is the main feeling, the feeling of shame, that they belong to a common creed unlawful, powerless, weak – and with the sense of the joy of life is mixed some dreary feeling of their own inferiority, a state of neglect before the mighty.

Whatever happened, whatever the fate of this city, I will not complain and I will not pity those, to whom the street corners, the banks, the ships and the warehouses belong. Alongside all of their Yugoslav tricolours, were also the Fiumani, and in their pre-war silence and chivalrousness were hidden the subterfuge and calculating attitude of the merchant, who goes just for the money. I won’t grieve for them nor for the legion of those, who over three lovely autumnal days cheered, sang and carried banners. I will only grieve for the pale little people, as their half-spoken “ča” chokes in the instinctive fear before the sharp glance of contempt and superiority…

Long, difficult months of waiting. Events, attacks, parades. Soldiers, soldiers, soldiers. Italians, French, Americans, English, Indo-Chinese. Ships, automobiles, aeroplanes. Carabinieri, bersaglieri, granatieri. Infantry, sailors, lancers, gunners. Crowded and mixed and multi-coloured. Smugglers, detainees, fugitives. And the inns and basements reverberate and glass shatters and girls scream, and blood, wine and champagne flow. Fiume goes crazy and howls and rages.

Yet that’s what it wanted and so sullenly and so sombrely. Like the shadows we loiter only around the corners and we disappear in the corners. Whilst the sun stings and the truth stings. However, the shame against man stings the most of all, for man, as he oppresses his own brother. Of all these people of various colours and uniforms the most likeable are the Annamese (Vietnamese from the French peacekeeping forces), yellow, silent, mysterious, calm creatures with a sick nostalgia for the East and a blunt lack of understanding for all of this colourful, noisiness and craziness. Why are they here and for what use is the secret, eternal pain for the motherland? The same feeling in them, that they protect us, and in us, that they protect. A feeling of pain, shame, submissiveness, disgrace.

Mornings and afternoons and evenings pass. And nights fall, long nights without sleep, when below the windows the hooves of horses clatter as they pass by, heavy cannons boom, the steps of soldiers reverberate. And the city stays silent and the river stays silent, and the sea, in a troubled uncertainty. Just above the houses glimmer the large, light letters: Viva Fiume italiana! And the shining sign and the shining star, so that the brothers can see on the other bank. And they in despair and hopeless expectancy hide their heads amongst the pillows, so they see nothing, so they hear nothing, so they feel nothing. And everything is dead, rigid, uneasy. And everything is sleepless yet in a dream, without a break, without rest, without peace, without joy.

It just sleeps like a fatigued beast, dreaming maliciously and in that sleep of new bites and stabs, the grey formless masses, Fiume sleeps, a city without soul and without physiognomy.

*******

Sva prava pridržana / All rights reserved.

Antun Barac (1894 Kamenjak near Crikvenica – Zagreb 1955) was an important literary historian and writer, who was an advocate for the publication of Janko Polić Kamov’s works. In 1917 he established the influential publishing institute ‘Jug’ in Zagreb with other writers. Amongst the books they planned to published was Kamov’s only novel Isušena Kaljuža written from 1906-1909, but this never happened.

Antun Barac (1894 Kamenjak near Crikvenica – Zagreb 1955) was an important literary historian and writer, who was an advocate for the publication of Janko Polić Kamov’s works. In 1917 he established the influential publishing institute ‘Jug’ in Zagreb with other writers. Amongst the books they planned to published was Kamov’s only novel Isušena Kaljuža written from 1906-1909, but this never happened.

Barac spent the unsettled period after the First World War from 1918-1924 in Sušak (the eastern part of today’s Rijeka) working as a professor at the secondary school. During this period he wrote this short, stark, even poetic essay Fiume, in which he describes the unpleasant events and experiences in the city of Rijeka at the time of the arrival of foreign peace-keeping troops whilst the city’s fate was being decided in post-war negotiations, and just upon the eve of the arrival of D’Annunzio and his soldiers. It is interesting to note that Barac was most likely reading the still as yet unpublished manuscript of Kamov’s Isušena Kaljuža during this period and that it may have influenced his writing of Fiume. This text was first published in the journal Njiva in 1919.

Barac was also the originator of the idea to publish a collection of the complete works of Janko Polić Kamov, which finally saw the light of day from 1956-1958, amongst which the novel Isušena Kaljuža was printed for the first time almost 50 years after Kamov wrote it.

Thanks to Igor Žic